Small Grants Spotlight: Abby Córdova & Natán Skigin

Author: Ayuko Picot

Theme: Displacement, Migration, & Integration

In today’s Small Grants Spotlight, we feature Abby Córdova and Natán Skigin, recipients of EGAP’s LATAM Regional Hub Small Grants Fund. Abby Córdova is an Associate Professor of Global Affairs in the Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame. Córdova holds a PhD in Political Science from Vanderbilt University. Natán Skigin is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame and a PhD Fellow at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies.

We spoke to Córdova and Skigin about their paper “Reducing Citizen Support for State Violence against Undocumented Immigrants through Victims’ Testimonies and Information Campaigns,” which is part of a larger project titled, “Reducing Anti-Immigrant Sentiment and Promoting Pro-Immigrant Behavior in Host Latin American Countries.” Their paper examines the effects of information campaigns combined with outgroups’ personal narratives on citizen attitudes towards the use of state violence against undocumented immigrants and increased demands for accountability. They found that individuals who were exposed to both information on the rule of law and immigrants’ testimonies became more compassionate towards immigrants, angrier towards state forces, and more willing to hold public officials accountable. We asked Córdova and Skigin about the intervention and findings from this project.

You conducted your research in Mexico, an in-transit country for many Central American migrants headed to the United States. Can you briefly describe the local population’s attitudes towards immigrants? How prevalent is the use of force against undocumented immigrants in Mexico?

Our fieldwork in Mexico City and on the Southern border, in the city of Tapachula, Chiapas, was important for identifying commonly held beliefs about immigrants and the types of interventions that could be effective in reducing discrimination. We confronted the reality that immigrants face in Mexico right after we landed in the city of Tapachula. The taxi driver who took us from the airport to the place where we were staying started telling us about how some immigrants can be dangerous, particularly if they are from Central America, indicating that people in local markets sometimes go after immigrants who are suspects of crime and take matters into their own hands. Besides portraying immigrants as criminals, many of our interviewees referred to the common belief that high immigration flows into a poor country like Mexico could deplete already limited resources.

From our qualitative interviews and baseline survey data from a three-wave panel, it is clear that in Mexico the beliefs that immigrants represent a security threat and an economic burden for the country are widespread among the population. Our findings resemble those from a 2020 survey by the Latinobarometer indicating that more than 65 percent of Mexicans believe that immigrants increase crime rates in the country, and over 60 percent consider that immigrants represent an economic burden for the state. These numbers are similar to what this survey finds in other countries in the region that have seen recent inflows of immigrants such as Chile and Colombia.

The use of violence against immigrants by state armed forces reinforces the negative stereotype that immigrants represent a security threat, despite abundant evidence demonstrating that this is not the case. Indeed, the Mexican government has implemented highly repressive tactics to contain immigration in its territory, deploying seven times more military personnel to curb immigration than to salient security issues, such as the trafficking of drugs and gasoline. By January 2022, Mexico had deployed as many as 28,397 state security agents to its Northern and Southern borders. The widespread use of state force against immigrants violates international laws, and abuses have been extensively documented by civil society organizations advocating for immigrants’ human rights.

For your intervention, you implement two strategies to reduce citizen support for state violence against undocumented immigrants. Can you elaborate on the strategies, and why you chose to focus on providing information on the law and immigrants’ testimonies?

A common idea is that individuals’ attitudes are driven by their prior knowledge—or lack thereof. Consequently, we reasoned that providing people with information about the rule of law and, specifically, that the state’s use of force against immigrants to prevent them from continuing their journey is unlawful might reduce citizen support for state repression. However, we also know from previous studies that offering accurate information updates citizens’ knowledge, but often does little to shape opinions. This begged the question of what kind of information might change citizens’ hearts and minds, but also whether other interventions could be more effective.

Theories in psychology claim that testimonies or personal narratives transport people into stories and thus tend to be more persuasive and reduce counter-arguing. Narratives also heighten audiences’ emotional reactions. For example, recent research shows that listening to personal experiences diminishes prejudice toward outgroups, even in hostile conflict settings. These findings resonated with our own experiences during fieldwork, as hearing about immigrants’ challenges first-hand was deeply moving. Accordingly, we tested messages containing information about the rule of law (i.e. how immigrants ought to be treated by state forces) and original testimonies we collected during our interviews in Mexico—in particular, the testimony from a Central American immigrant who was wounded by Mexican security forces who obliged him to jump from a bridge, ending up with multiple injuries and a broken leg.

The project was a result of a collaboration between the research team and an international humanitarian organization. How and why did you establish this partnership?

In the fall of 2021, Skigin was conducting interviews for his dissertation, in which he studies how to increase political solidarity toward victims of gross human rights abuses in Latin America. One of those interviews was with the head of the communications team of a global humanitarian organization. He wanted to understand how they crafted their media campaigns to foster empathy. As the conversation moved forward, it became clear that Skigin could collaborate with this organization by testing whether their campaigns were successful or not. At some point, however, his interviewee suggested also testing their media campaigns on immigration. Since we were both interested in the topic of attitudes toward immigrants, this was a great opportunity to work together with the humanitarian organization to test the effects of real-life media campaigns focused on promoting pro-immigrant attitudes.

Afterwards, the humanitarian organization sent us a wide range of videos they had used during their campaigns and those that they were planning to disseminate on social media for the first time. After reviewing them, we selected those that matched our theoretical insights drawn from previous literature and our fieldwork, including the informational video for this paper as well as others we use as part of the larger project, including a video that demystifies the idea that immigrants are criminals, but rather are fleeing violence.

In what ways did the combination of informational messages and immigrants’ testimonies as opposed to information-only or testimony-only messages reduce support for state violence and increase demands for accountability?

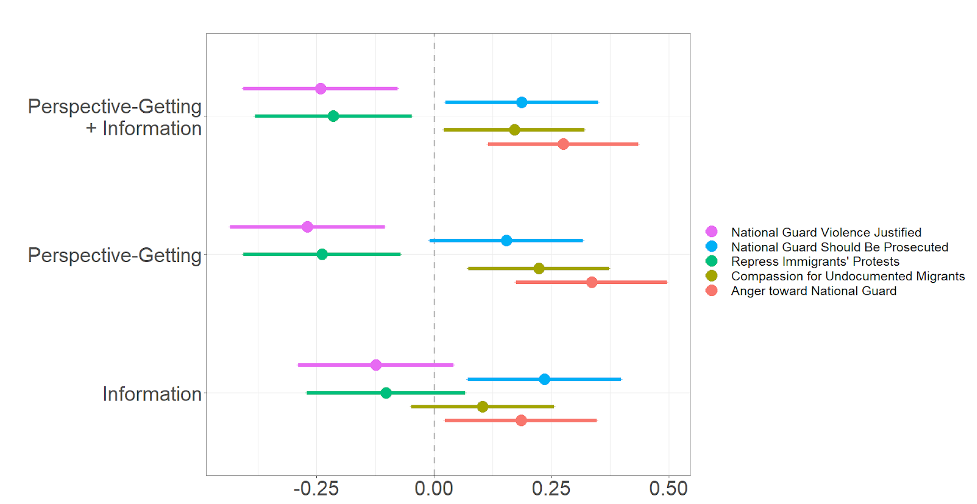

Providing information about the unlawful nature of the use of force against immigrants increased participants’ agreement with the judicial system prosecuting National Guard agents who use force to prevent the entry of undocumented immigrants into Mexico. Learning about immigrants’ rights and the restraints imposed by the law on security officers also elicited anger toward state perpetrators. However, it did not elicit compassion toward immigrants nor reduce support for state violence.

In contrast, the immigrant’s testimony (our “perspective-getting” intervention) reduced support for state violence against immigrants’ caravans and protests while also inducing compassion for immigrants and anger towards state officials who repress them. However, because the testimony did not convey any information about whether the behavior of security forces was lawful or not, it did not change participants’ willingness to hold them accountable.

Only when survey respondents heard about immigrants’ experiences with state victimization first-hand and learned that the use of force against immigrants to contain undocumented immigration is unlawful did they express lower support for state violence, greater support for holding the National Guard accountable, and greater compassion for immigrants and anger toward perpetrators. Figure 1 summarizes these results.

Figure 1. Average Treatment Effects on Dependent Variables

In short, our results suggest that educating the public about the law and immigrants’ rights is not enough for reducing support for state violence and generating pro-social attitudes toward undocumented immigrants. A holistic approach to reduce citizen support for state violence and increase demands for accountability requires disseminating information about the law and hearing from the victims themselves about their experiences with state abuse.

What are the implications of these findings on humanitarian organizations advocating for citizen support for the rights of undocumented immigrants?

Our larger project entailed testing the effects of media campaigns that included immigrants’ testimonies—adopting a “perspective-getting” strategy. Across experiments, we found that personal narratives, including those aimed at dismantling the stereotypes that immigrants increase crime and are an economic burden, result in more inclusionary attitudes and behaviors. For example, our experiments containing personal narratives countering the belief that immigrants are criminals resulted in higher support for granting access to basic services to immigrants, such as health and education, and a higher probability of intending to vote for a political candidate supportive of immigrants’ integration. In sum, across studies we find that personal narratives are powerful for bringing about pro-immigrant support. In this particular paper, seeking to reduce support for state violence and increase demands for justice, we combined personal narratives with an information treatment and found that these interventions complement each other. Taken together, therefore, our findings indicate that humanitarian organizations’ media campaigns have great potential to foster durable attitudinal and behavioral change, particularly if their messages combine personal narratives and factual knowledge correcting misperceptions.