Small Grants Spotlight: Loreto Cox & Natalia Garbiras-Díaz

Author: Ayuko Picot

Theme: Democracy, Conflict, & Polarization

In today’s Research Grant Spotlight, we feature Loreto Cox & Natalia Garbiras-Díaz, recipients of EGAP’s Priority Theme Small Grants Fund. Cox is Assistant Professor at the School of Government at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. She received her PhD in Political Science at MIT in 2019. Garbiras-Díaz received her Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley in 2021. She is currently a Max Weber Postdoctoral Fellow at the European University Institute and will start as Assistant Professor at Harvard Business School’s Business, Government and the International Economy unit in Fall 2023.

We spoke to Cox and Garbiras-Díaz about their project, “The nature, sources, and consequences of citizens’ anti-establishment sentiments: Evidence from two Latin American countries.” Their project examines the sources of citizen anti-establishment sentiments and how such sentiments influence political attitudes and behaviors in Colombia and Peru. Using a priming experiment to elicit anti-establishment sentiments, they find that heightened anti-establishment sentiments reduce trust in institutions, though these sentiments do not affect citizens’ democratic attitudes. Moreover, heightened anti-establishment sentiments increase the likelihood of citizens to request information about polling stations and to vote in Colombia. Finally, citizens with anti-establishment sentiments were more likely to support candidates with anti-establishment appeals. We asked Cox and Garbiras-Díaz about their survey experiment and findings from this project.

In an effort to distinguish anti-establishment sentiments from populism, you provide a unique operational definition of citizen anti-establishment sentiments. What is your definition, and what distinguishes this concept from populism?

Our definition of citizens’ anti-establishment sentiment includes three components: first, anti-elitism, which we measure as how negatively citizens evaluate politicians. Second, distrust of political parties, which refers to the institutional dimension of anti-establishment sentiments. The third component is anger toward the political elites, which helps distinguish anti-establishment sentiments from ordinary criticism of the functioning of democracy.

As for populism, contemporary studies mostly adhere to the ideational approach elaborated by Mudde (2004), who defines populism as consisting of three sets of ideas: a Manichean and moral cosmology that divides the world into the good and the evil (Manicheism); the proclamation of “the people” as a homogeneous and virtuous community (people-centrism); and the depiction of “the elite” as a corrupt and self-serving entity (anti-elitism). Thus, citizen anti-establishment sentiments and populism share the “anti-elitist” component, but differ in their other two components. As it turns out, our study shows that anti-establishment sentiments and populism are correlated, but only to a moderate extent (the correlation between the indexes that average the three components in each case is 0.48, not too high considering that they share one out of three components). We also find that anti-establishment sentiments are much more widespread than populism in our case studies.

You chose to focus on two countries, Colombia and Peru, where anti-elitism, distrust of political parties, and anger against politicians are widespread. Tell us a bit more about the prevalence and main sources of citizen anti-establishment sentiments in Colombia and Peru leading up to the 2022 presidential elections and local elections respectively.

Indeed, if we go component by component, about half of our respondents in both countries rate politicians at the minimum, more than half report the minimum level of trust in political parties, and about a third report the maximum level of anger toward politicians. We construct binary indices that indicate that 53% of Colombians and 56% of Peruvians have anti-establishment sentiments.

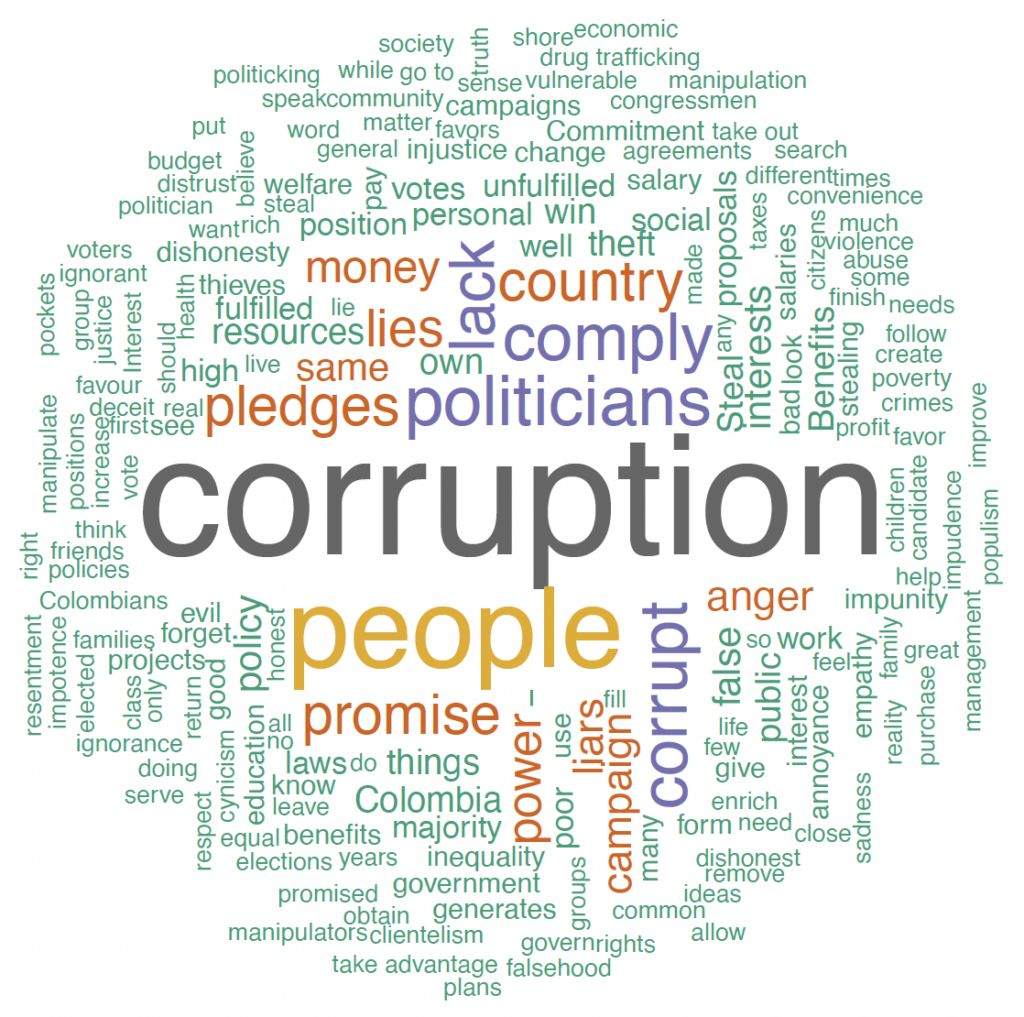

To further explore the sources of such anti-establishment sentiments, we use the responses to an open-ended question asking what makes respondents angry at politicians, which is also the question we use to experimentally elicit anti-establishment sentiments (we will come back to this later). Text analysis reveals that citizens cite corruption first and foremost as a reason for such anger, followed closely by politicians’ unfulfilled promises (see Figure AA). While corruption is often identified as a force behind the rise of anti-establishment parties (e.g., Hanley and Sikk 2016), we believe that politicians’ broken promises as a driver is a more novel finding that deserves further attention.

Fig. AA. What makes citizens angry at politicians? Wordcloud from responses to the treatment prompt

What do your findings suggest are the causal effects of anti-establishment sentiments on democratic attitudes, electoral engagement, and attitudes towards candidates?

We relied on a priming survey experiment in which we randomly assigned half of the sample to receive an open-ended question about what makes them angry at politicians (while the control group received a placebo question) in order to obtain a causal purchase on the effects of anti-establishment sentiments. We felt that this was the most appropriate way to manipulate anti-establishment sentiment for reasons we detail in the paper, particularly ethical and design considerations.

The priming question did indeed increase anti-establishment sentiment, as our manipulation checks show. We find no effects on a wide range of questions about democratic attitudes. However, we do find reduced trust in institutions.

We also test for effects on electoral engagement, measured by intended turnout and by a behavioral question asking whether respondents wanted to receive information about their polling station. In Colombia, both measures suggest that anti-establishment sentiments have a mobilizing effect, while in Peru we find no such effects.

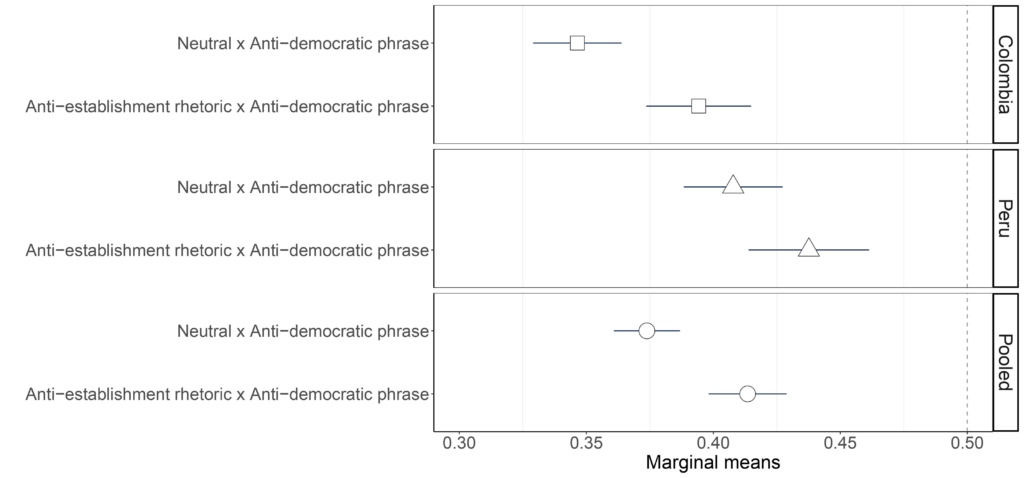

Finally, interested in exploring voter responses and given the highly polarized elections around which we conducted our surveys, we also included a candidate choice (conjoint) experiment in which one of the varying attributes of the candidates was anti-establishment appeals in the form of “candidate slogans.” We find that anti-establishment candidates enjoy an electoral advantage (in terms of both the estimated AMCE and the marginal mean of this attribute), driven mainly by respondents whose anti-establishment sentiments were previously enhanced by our prime treatment [see Figure AB]. In other words, this finding suggests that in contexts of heightened anti-establishment sentiments, candidates benefit from using this type of rhetoric. We argue that such a context better reflects the real-world informational environment in which citizens make voting decisions. Campaigns are increasingly plagued by anti-establishment appeals made by candidates interested in mobilizing disenchanted voters around their dissatisfaction and anger with the political establishment.

Fig. AB. Conjoints’ estimated marginal means by sample and treatment condition in prime experiment

Heightened anti-establishment sentiments led to increased electoral engagement in Colombia, where voting is voluntary. In Peru, where voting is compulsory, anti-establishment sentiments did not have the same mobilizing effect. Can you elaborate on this?

Yes, when voting is compulsory, one can expect less movement in the intention to turn out to vote, since failure to vote is often punished with a fine (as in Peru). The turnout rates in our two experimental sites reflect these different electoral rules: while 77% voted in the Peruvian election, 55% voted in the first round of the Colombian presidential election. Translated to our study, this means that there was a larger margin to be mobilized in Colombia than in Peru, which is consistent with what we found.

Based on your research, what are the implications of the growing rise in citizen disillusionment and rise of anti-establishment candidates on democracy?

Our research design was aimed at identifying the sources and effects of anti-establishment sentiments on citizens’ political attitudes, so an answer to this question is necessarily more speculative. However, we do have some insights into some possible consequences, some of which are supported by some additional tests we conducted in our experiment.

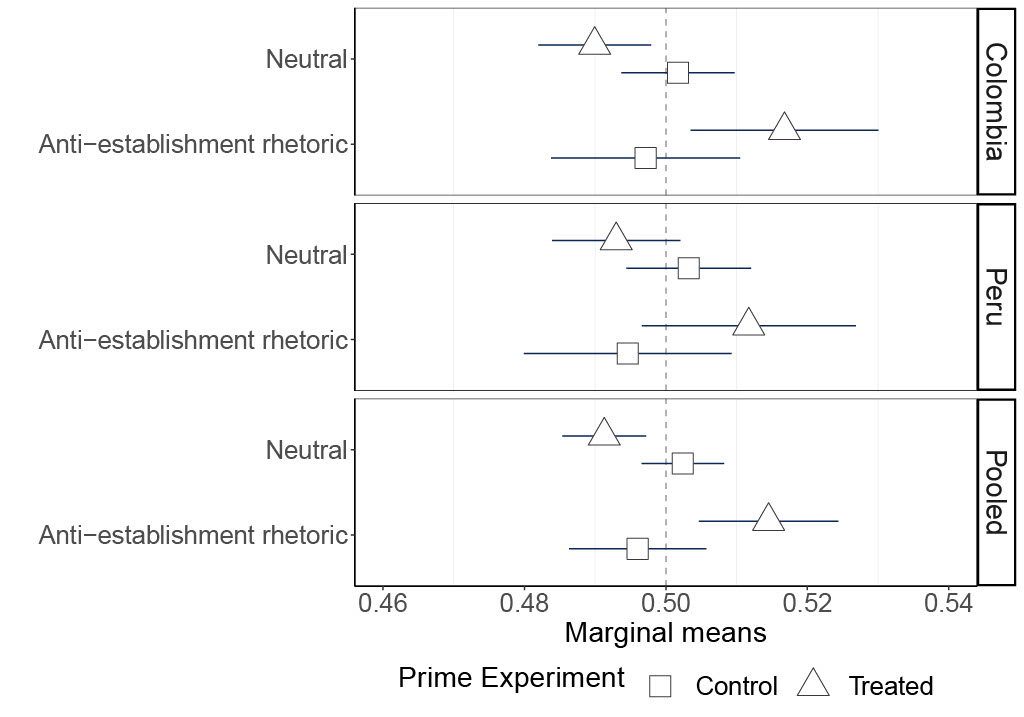

Focusing on the region we study, Latin America, our evidence suggests that the conditions that drive anti-establishment sentiment are ripe there: major corruption scandals (such as the more prominent case of Odebrecht) and weak party systems (e.g., Levitsky at al. 2016, Lupu 2016). Thus, given the results of our conjoint experiment, this context provides an ideal environment for anti-establishment political outsiders to make breakthroughs in mobilizing voters by increasing their anti-establishment sentiments. This creates space for a class of unconstrained political entrepreneurs – who certainly do not constitute the universe of electoral challengers in the region – to win office, often with poor records of democratic governance. Recent elections of anti-establishment candidates such as Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, and the recently impeached former president of Peru, Pedro Castillo, support this view. However, to explore this possibility in a more systematic way, in addition to anti-establishment rhetoric, we include anti-democratic positions as a separate attribute characterizing candidates in the conjoint experiment, which we frame as “famous phrases”. We find that subjects treated with the prime experiment, and thus whose anti-establishment sentiments have been heightened, are statistically less likely to punish anti-democratic rhetoric when the candidate also uses anti-establishment slogans. This suggests that anti-establishment sentiments may undermine the viability of citizens as a check on democracy.

Fig. AC. Estimated marginal means by sample and treatment condition in the prime experiment (interaction between anti-democratic phrases and either neutral or anti-establishment profiles)