Brief 77: When Does Information about Corruption Help or Hurt Incumbent Parties? Exploring the Importance of Prior Beliefs in Mexico

EGAP researchers: Eric Arias, Horacio Larreguy, John Marshall, and Pablo Querubín

Key takeaway: Prior beliefs are important in how voters digest and react to information about politician corruption. Using a simple learning model, the authors show that the effect of information about candidate malfeasance depends on voters’ prior beliefs. In cases where citizens believed that their incumbent engaged in even higher levels of corruption than the ones revealed, they might update their beliefs positively and become willing to turn out for the incumbent or switch their vote to the incumbent. Understanding how prior beliefs interact with informational interventions is then important for policy-makers in designing and scaling political accountability interventions.

Geographical Region: Latin America and the Caribbean

Type of study: Field experiment

Preparer: Catlan Reardon

Executive Summary

Corruption and malfeasance among politicians can threaten effective policy-making by negatively impacting the livelihoods of vulnerable citizens. A broad literature points to information as an important tool that policy-makers and practitioners can use to increase political accountability. However, many studies have shown that revealing information about malfeasance does not necessarily decrease incumbent support.

The authors develop a Bayesian learning model that illustrates that the effect of information on turnout and vote choice depends on citizens’ prior beliefs. To test the model’s predictions, the authors conducted a field experiment in Mexico in which they informed voters in randomly-selected electoral precincts about malfeasance spending before the 2015 municipal elections. The results show that audit information does not decrease incumbent vote share if voters already believed their incumbent was sufficiently corrupt. In cases where the audit reports led citizens to update their posterior beliefs more positively, the intervention increased incumbent vote share. Lastly, the authors find that less surprising information led to reduced turnout, while extreme levels of malfeasance—either very low or high—mobilized citizens to turn out to vote.

This project formed part of EGAP’s Metaketa I initiative focused on information and accountability.

Policy Challenge

Across much of the world, elected politicians are responsible for implementing policies that can have significant impacts on the welfare of citizens. Politicians often have wide discretion about how and where funds aimed for poverty reduction are spent. Yet, corruption remains rife within these programs—including bribery, fraud, and misallocation. An important first step in increasing political accountability is for citizens to elect honest politicians and vote out those that misuse the office to their own ends.

Political accountability, it is often argued, hinges on the presence of an informed citizenry. More informed citizens, in theory, will be better equipped to screen out or sanction politicians engaging in corruption or with poor performance records (e.g., Barro 1973; Ferejohn 1986; Rogoff 1990; Fearon 1999). While some empirical studies show that providing information about incumbent performance can increase electoral accountability, many studies do not. Moreover, much of the evidence is mixed as to the mechanisms behind voters’ response: it is unclear whether the interventions that do induce electoral sanctioning stem from voters updating their beliefs about politicians (i.e., the “voter learning” mechanism), or from other mechanisms such as a public signal coordinating votes toward higher performing candidates (e.g., Arias et al. 2019) or the reactions of the candidates themselves (e.g., Banerjee et al. 2011; Cruz et al. 2021). Understanding the mechanisms behind information dissemination campaigns is key for policy-makers to design effective interventions aimed at improving political accountability.

Context

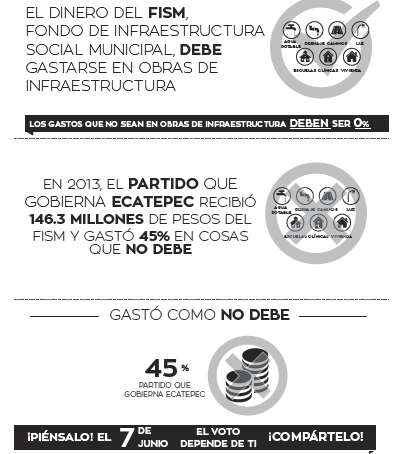

The study was conducted across four states in Mexico during the 2015 municipality elections, which were held concurrently with federal legislative elections. Mexico is composed of 31 states along with Mexico City, and includes around 2,500 municipalities and 67,000 electoral precincts. Municipal governments in Mexico are responsible for providing basic public services and managing local infrastructure. These municipalities are governed by mayors who, at the time of the intervention, were elected to three-year nonrenewable terms, with elections typically dominated by one or two parties. The intervention focuses on the Municipal Fund for Social Infrastructure (FISM), which are direct transfers that are earmarked for infrastructure projects for those living in poverty and are subject to independent audits. In Mexico, citizens both have low expectations about politician performance and are not well-informed about the resources available to mayors (Chong et al. 2015).

Research Design

The authors conducted a field experiment to test their hypotheses about the role of prior beliefs on the effectiveness of information on electoral accountability. The field experiment was implemented across 26 municipalities in Mexico during the 2015 municipal elections. Partnering with a civil society organization, Borde Politico, the authors circulated non-partisan leaflets outlining the results of independent municipal audit reports across 678 electoral precincts. (Read more about this researcher-practitioner partnership here.) The leaflets contained one of two different measures of malfeasance: (1) the proportion of unauthorized spending, or (2) the proportion of spending that did not benefit the poor.

The authors draw from two data sources to measure their core outcomes. First, they use publicly available electoral returns from each sampled precinct to measure incumbent vote share and turnout. Second, they conducted a survey following the election with approximately 10 voters from each of the treated precincts and ten voters from a randomly selected control precinct within the same block. Due to resource constraints, the authors use the municipal control group’s beliefs measured in this survey to proxy for pre-treatment prior beliefs of voters within each municipality. They provide various pieces of evidence suggesting that post-election beliefs in the control group are likely to serve as good proxies for pre-treatment beliefs in treated and control precincts.

Results

The authors find that, in the average treated precinct, providing audit information increased incumbent vote share by two percentage points. Since posterior beliefs were not affected on average, increased support for the incumbent is unlikely to reflect belief updating in a particular direction. Rather, their exploratory analyses suggest that this was likely due to voters choosing the less risky option, rather than a reflection of changes in incumbent or challenger behavior.

More importantly, in line with their theory, the authors also find significant heterogeneity in response to treatment that depended on voters’ prior beliefs about incumbent malfeasance. First, they find that voters updated their posterior beliefs in light of information: those voters who possessed pre-existing expectations of high corruption updated their beliefs about the incumbent favorably, while those with more positive prior beliefs shifted their beliefs about the incumbent negatively in light of malfeasance information. In addition, voters with weak prior beliefs are more likely to update their posterior beliefs about the incumbent candidate.

Second, the authors find that the increase in incumbent vote share was largest among voters who updated their posterior beliefs about the incumbent party favorably. In particular, revealing information that the level of incumbent malfeasance spending was below 35% (i.e. low levels of corruption given baseline beliefs among citizens) significantly increased the incumbent’s vote share. Relatedly, the effect of revealing poor performance on vote share decreases with the extent to which voters updated their perceptions of incumbents unfavorably.

Finally, there exists a non-monotonic effect of revealing malfeasance on voter turnout. That is, relatively unsurprising information led to around a 1 percentage point decrease in turnout, while extreme cases—both 0% and above 50%—increased turnout by around 0.5 percentage points. This finding challenges the assumption that providing information about bad behavior in office will lead to general disengagement among voters. Rather, vote choice and turnout depends on citizens’ prior beliefs about their incumbent party.

Taken together, the authors argue that the average effects of information provision interventions can mask significant heterogeneity in posterior belief updating, vote share, and turnout conditional on what voters’ prior beliefs are.

Lessons

Overall, the results demonstrate the importance of voters’ prior beliefs in understanding the conditions under which information can affect electoral outcomes. In many developing contexts, citizens hold pessimistic views about the performance of their politicians. In light of this study’s findings, this reality has important implications for information dissemination campaigns. Without taking into account citizens’ prior beliefs, revealing incumbent malfeasance can have the perverse effect of sustaining these politicians in power–as well as potentially weakening incentives for worse-performing politicians to serve voters. Furthermore, the results highlight the need to improve voters’ expectations of their elected representatives and the importance of understanding how and why voters’ prior beliefs are out of sync with reality.