Small Grants Spotlight: Uchenna Efobi

Author: Ayuko Picot

Theme: Climate Change Governance

In today’s Small Grants Spotlight, we feature Uchenna Efobi, a recipient of EGAP’s Priority Theme Small Grants Fund. Efobi is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy and Development Research based at Covenant University in Nigeria. He is also a Research Fellow at the Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa. Previously, he served as Faculty at Covenant University and a Research Fellow at the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa at the University of Ghana. Efobi holds a PhD in Management Science from Covenant University.

We spoke to Efobi about his project, “Shifting Smallholders’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Farming Practice for Climate Justice in Nigeria: A Survey Experiment.” Efobi’s project examines the effects of an informational intervention on engagement in bush-burning practice, a common farming practice amongst rural farmers that contributes to pollution and climate change. The intervention involved exposing study participants to adverse social and economic consequences of bush-burning in five Nigerian states. Efobi finds that the exposure to this information increased participants’ perceptions of bush-burning as an unacceptable practice and reduced their likelihood of engaging in such practice in the next planting season. We asked Efobi about the intervention and findings from this project.

What is the practice of bush-burning, and why is reducing this practice important for climate change?

Uchenna Efobi: Agricultural burning, which includes field flaming, crop stubble, and bush-burning, is a ubiquitous practice among low-income rural farmers in Nigeria. About 2 of every 3 farmers in this study’s context have engaged in this practice in the previous planting season, and a similar proportion says this practice is acceptable. They believe that agricultural burning hastens the planting cycle and enhances weed and pest/disease control. Many farmers also view the practice as a cheaper method for farmland clearing before cultivation than alternative methods.

The environmental consequences of bush-burning are enormous: it is one of the largest carbon emitters, second to emissions from the energy sector in Nigeria. It is also responsible for more than a third of all black carbon emissions and linked to the melting cryosphere. Hence, the continuance of this practice challenges the realization of sustainable development in Nigeria.

For this project, you collaborated with the Institute for Entrepreneurship and Development Studies at Obafemi Awolowo University. Were you already in collaboration with them before this project began, or did you establish the partnership in order to answer the questions raised in this project? Were there any obstacles in implementing this intervention?

UE: I had an informal relationship with the Institute for Entrepreneurship and Development Studies at Obafemi Awolowo University before this project. However, our relationship was further strengthened with the execution of this project, as the institute was instrumental in the successful execution of the fieldwork, including securing the IRB.

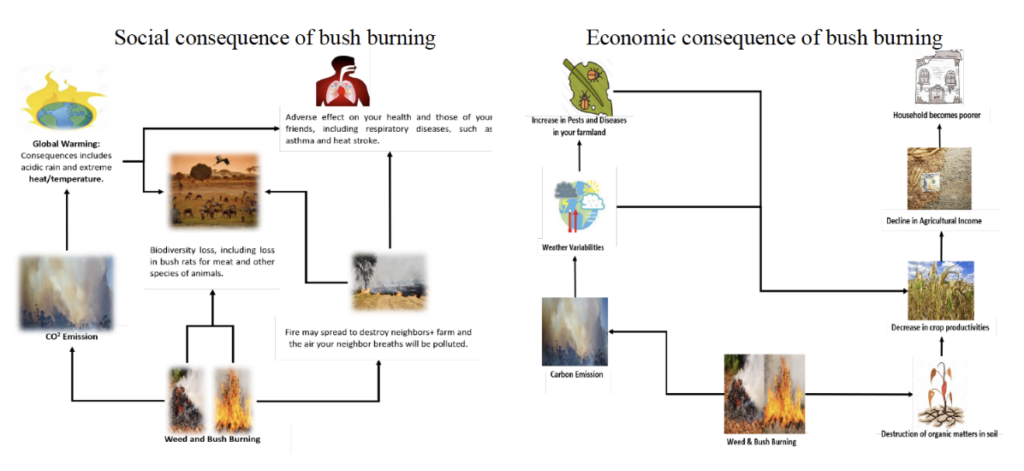

The main obstacle during the implementation of this intervention was language constraints. Our intervention provided statements curated as a newspaper article highlighting the social and economic consequences of agricultural burning. Since the study’s sample consisted of farmers with low levels of education living in rural areas within five states of Nigeria, we faced challenges in getting the information across. My implementing partner, the institute, and I collaborated to circumvent this constraint by transcribing our research instrument to local languages and deploying cartoon expressions of the intervention’s information (see diagrams below).

This study tests the effects of an informational exposure on long-term adverse consequences of bush-burning. What were the primary findings from this project?

UE: Exposing farmers to information about the adverse consequences of bush-burning led farmers to view this practice as unacceptable and lowered their self-reported likelihood of engaging in such practices in the next planting season. This pattern was consistent for farmers in all three treatment groups. However, farmers, who were exposed to the economic rather than social consequences of bush-burning, were significantly more willing to pay for local government interventions aimed at supporting sustainable farming practices.

Our findings also highlight the potential of such low-cost interventions to change rural farmers’ perception of the causes of climate change. Farmers, who were exposed to the information, were more likely to agree that human activities are a driver of climate change. This perception shift as a result of our intervention is striking in a context where there is almost a universal anti-science consensus about the causes of climate change.

You observed stronger effects on attitudinal and behavioral changes amongst study participants who received information on adverse economic consequences, compared to participants who received information on social externalities. What explains these differences?

UE: The stronger effects observed for farmers who received information about the adverse economic consequences (rather than social consequences) may be because farmers negotiate the pecuniary costs of the consequences of their current actions. Farmers are willing to adjust their behaviors, assuming their actions have economic consequences. 73% of these farmers are either poor or extremely poor, and 71% do not have enough money for food or are barely able to feed and clothe. Hence, it is not surprising that highlighting the monetary costs of bush-burning is more influential as revealed in this study’s findings.

Based on these results, what are the policy implications of these findings on climate change mitigation through sustainable farming practices?

UE: A relevant policy action could be providing incentives for farmers to reduce agricultural burning, but there is currently no such policy consideration in Nigeria. Instead of only aiming Nigeria’s agricultural policy towards improving farm yield through input support, encouraging sustainable farming practices through monetary incentives could be incorporated with an information campaign to educate farmers about the consequences of agricultural burning. This policy is urgent in the Nigerian context, which is a melting pot for the diverse drivers of pollution causing climate change, ranging from crude oil spillage, pollution from crude oil drilling, and carbon emission from agricultural activities.