Mercury Project Spotlight: Maarten Voors

In this Mercury Project Spotlight, we feature EGAP member Maarten Voors, who is also a member of the EGAP Advisory Committee for the Mercury Project: Health Ambassadors. This project is a research collaboration between Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP), Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR), and the Centre de Recherche et d’Action pour la Paix (CERAP).

The project studies strategies to increase public fluency and confidence in reliable scientific information about COVID-19 and COVID vaccine uptake through a “health ambassadors” outreach initiative. The intervention consists of a “health ambassadors” program in which ambassadors trained on engaging individuals about vaccine risks and benefits will proactively engage households and offer a direct and private opportunity to discuss concerns. The randomized controlled trials will be implemented in four Anglophone and Francophone countries in sub-Saharan Africa – Côte d’Ivoire, Malawi, Senegal, and Zimbabwe.

We spoke to Maarten to learn about his working paper, “Solving Last-Mile Delivery Challenges is Critical to Increase COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial.” The study examines the effects of access to COVID-19 vaccines on vaccine uptake in Sierra Leone, where it takes an average person three hours to get to a vaccination center each way. The intervention involved bringing vaccines to rural villages in Sierra Leone using mobile vaccination teams combined with either individualized door-to-door outreach or small group discussions. The research team finds that improving access to vaccines increased the community vaccination rate by 20 percentage points within just 48-72 hours. We asked Maarten about the intervention and how the findings from this study might inform the Health Ambassadors project.

Please describe the context of COVID-19 in Sierra Leone going into the project. What were the main challenges the project aimed to address? What evidence informed how you designed the intervention? Why did you focus on rural areas and the last mile approach?

Maarten Voors: Across low income countries (LIC), COVID-19 vaccination rates remain low. More than two years after vaccines became available, in many African countries vaccination rates are still in the single digits. At the time when we designed our study, several explanations were put forward as to why vaccination rates lagged behind high income countries. In terms of the global distribution efforts, vaccines tended to go to richer countries and those with geopolitical importance. One striking observation was that in some case when vaccines did reach LICs, they were not reaching people. It was argued that this was perhaps due to high rates of vaccine hesitancy. In a multi-country study, with EGAP members Alexandra Scacco and Macartan Humphreys, and other researchers, we documented that this was not true. Across 15 samples in 10 countries, we found that COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates were high (on average about 80%) and well above levels in USA or Russia.

In settings like Sierra Leone, simple issues like roads and rivers have a major impact on many development outcomes including health access. Especially in rural places, distances to clinics are large (in terms of time, miles and costs) preventing people from seeking care when needed. In many rural parts of Sierra Leone, it takes on average 3 hours to get to a vaccination center each way, and it costs 6.5 USD each trip. Thus, the study we designed was meant to be a proof-of-concept study, to learn that if these “last mile” type barriers are lifted, vaccination rates increase.

How did you work with the implementing partner to design and implement the intervention?

MV: We co-designed our intervention with the Ministry of Health and Sanitation of Sierra Leone and an international NGO, Concern Worldwide. Increasing vaccination rates, not just for COVID-19, is a priority of the ministry. We raised funds from the Weiss Asset Management Foundation, which allowed us to implement a large- scale cluster randomized control trial in 150 villages during spring 2022. In 100 villages, the Ministry of Health sent trained health teams, consisting of nurses and community social mobilizers. The teams held community meetings with leaders and the wider village population to introduce the vaccination campaign that would last 2-3 days in a given village. Each day, nurses set up an administration and registration infrastructure in the center of the village. Social mobilization teams went out to either visit homes to allow people to ask questions about the vaccines in private, or visit specific areas where they expected to encounter groups of people (around religious buildings, eating places, water sources, farm huts, etc.).

What were the results of the interventions on vaccination rates? What were the results from village meetings versus face-to-face interactions?

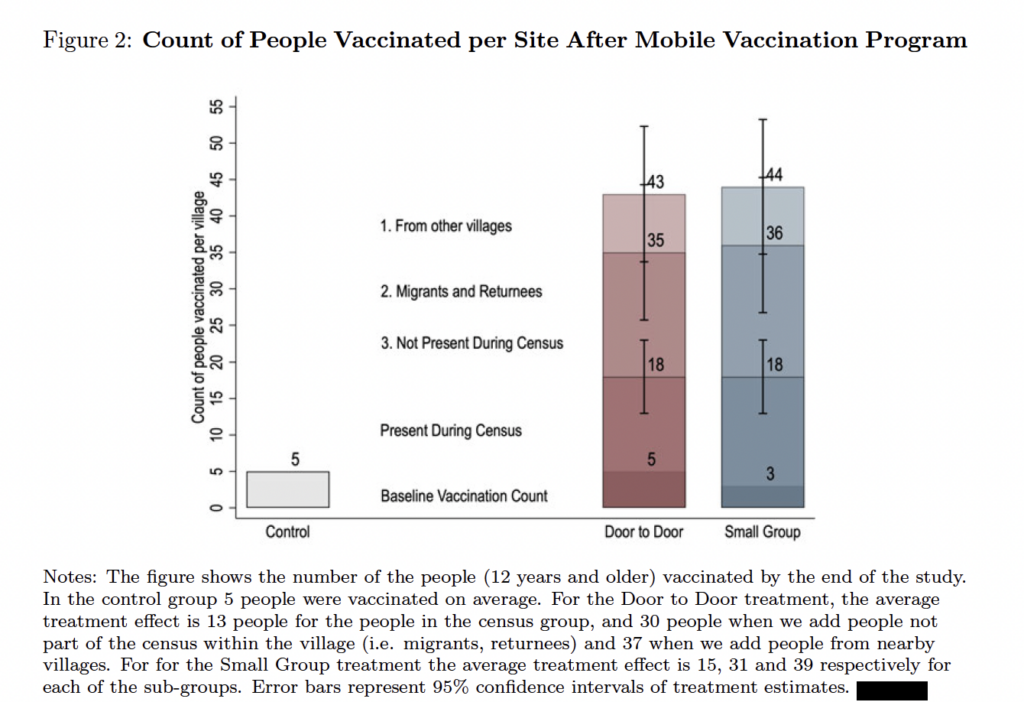

MV: We find that the vaccination rates in villages increase from on average 6% to about 29%, a very large increase of 23 percentage points. Compared to other studies we looked at, our results are larger than about 90% of the treatments reviewed. What is more, this increase in the vaccination rates is an underestimate of the total number of vaccines administered. During the vaccine drive, other groups of people showed up: residents of other nearby villages; recent migrant returnees who were not present during the village census (i.e. defining our denominator); and any other village resident missed during the census. The total number of people vaccinated per villages increased from about 9 to 55 people in treatment villages. Despite the remote locations and high travel costs (about 50% of our implementation budget), we are more cost effective (at 32 USD per shot) than most studies we reviewed.

We find no difference between the two types of social mobilization, so our study cannot really speak towards which strategy was more effective. We know that the village meeting may have played an important role in generating demand: about half the village was present at these meetings. There is a very strong correlation with take up – over 85% of those who chose to attend the meeting subsequently chose to get vaccinated. Of course, this is not a causal effect: people who were already interested in getting vaccinated may have been the ones who chose to attend the meeting, but it is encouraging. We also learned qualitatively that the private discussions with health staff were greatly appreciated. We also see knowledge and beliefs in the effectiveness of vaccines increased. Unfortunately, we did not collect systematic data on implementation factors like “effort” of health staff or the “quality of interactions” with villagers. Field notes from our field coordinators indicate no appreciable differences in the implementation effort or quality between the treatment arms. Of course, despite our observations and elaborate training, implementation factors could explain our null finding on the marginal effect of home visits.

What are some of the key lessons learned from this project that you find applicable to the EGAP Health Ambassadors project funded by SSRC’s Mercury Project?

MV: In essence, the Health Ambassadors project greatly complements our work. The Health Ambassadors project is being implemented in places where vaccines are accessible, so access is less of an issue. The scope of the project consists of using the voice of science, the opportunity to interact with health experts, being able to voice concerns in private, and to ask follow-up questions. Most campaigns that aim to understand vaccine hesitancy have relied on sending messages to people without allowing for interaction. While we could not unbundle the types of demand generation effects in our Sierra Leone study, if offers a promising starting point.