Brief 81: How non-partisan social media ad campaigns can improve electoral accountability

EGAP researchers: John Marshall, Horacio Larreguy

Other researchers: José Ramón Enríquez, Alberto Simpser

Key takeaway: Social media advertising can promote electoral accountability by informing voters about the performance of incumbent politicians. Online information campaigns, especially when they reach a large proportion of the electorate, persuade both those who directly engage with the information and those who encounter it indirectly through interactions with other voters.

Geographical Region: Latin America

Type of study: Field experiment

Preparer: Mark Williamson

Executive Summary

This study investigates whether a non-partisan informational campaign revealing incumbents’ performance to voters can help them to elect better politicians. The authors randomly exposed social media users in Mexican municipalities to paid advertisements describing the results of recent financial audits of their local government. Areas that were targeted with these ads were significantly more likely to vote for the municipal incumbent party where the ads reported good fiscal performance and slightly less likely to support the incumbent where the audit revealed financial irregularities in local government spending. These persuasive effects spill over to voters in parts of the municipality not targeted with the ads. These effects of directly and indirectly targeted ads are stronger when a large proportion of the electorate is exposed to the ads on social media.

Policy Challenge

The evidence that factual information about incumbent performance can help voters to reward high-quality politicians and sanction those that engage in corruption or negligence is mixed. The most promising findings emerge from interventions that reach large fractions of the electorate, but little is yet known about whether or why such high saturation campaigns are more likely to change votes. Social media has been proposed as one way to quickly and inexpensively disseminate the information needed to facilitate this kind of electoral accountability. While some experimental studies have investigated the use of social media advertising for these purposes, there remain open questions about how best to implement such a campaign: How many voters need to be targeted? Do online ads persuade voters who aren’t directly targeted? This study takes up these questions.

Context

Financial malfeasance is common in Mexican municipalities. Between 2008 and 2019, independent government audits of federal social infrastructure grants found that 17% of municipal grant expenditures exhibited irregularities. These irregularities often reflect corruption, including kickback schemes, preferential contracting, and embezzlement, or reallocation to projects benefitting less marginalized constituents. However, most citizens remain unaware of the results of these audits due to a lack of media coverage and engagement, reducing their ability to electorally sanction malfeasant incumbents. For similar reasons, voters may also not know when their politicians oversee sound fiscal management, thus preventing them from reelecting high-quality incumbents.

To address this gap in awareness, Borde Político—a non-partisan Mexican NGO promoting government transparency—has used informational campaigns to inform voters about the results of the audits in their municipality. For this study, the authors partnered with Borde Político to experimentally test the impact of 26-second paid-for video ads that were fielded on Facebook in the week preceding the 2018 municipal elections. The ads targeted users in particular municipalities and used infographics to report the percentage of expenditures with irregularities based on each municipality’s most recent audit by Mexico’s Federal Audit Office (ASF).

Research Design

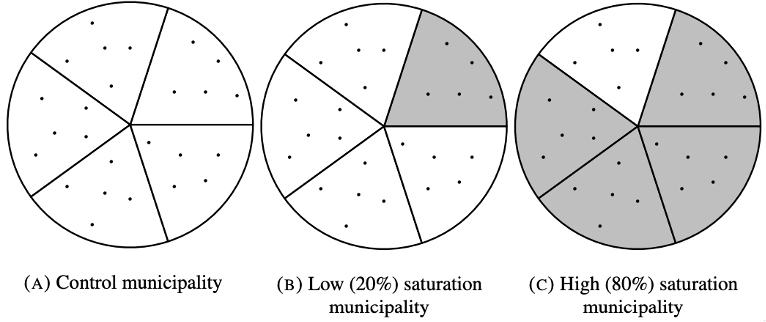

To evaluate the impact of Borde Político’s informational campaign, the authors randomized the targeting of Facebook users both across and within municipalities. The two-level randomization procedure begins by identifying blocks of three similar municipalities, almost all with mayors from the same incumbent party (see EGAP’s methods guide on block randomization). Within each of these blocks, municipalities were randomly assigned to either (A) a control condition where no Facebook users received Borde Político’s ads; (B) a “low saturation” condition where ads were targeted to all adults in 1 out of every 5 equally-sized geographical segments within the municipality; and (C) a “high saturation” condition where the ads targeted all adults in 4 out of every 5 segments within the municipality. The figure below explains the three conditions graphically, with each dot representing a polling station and shaded segments indicating “treated” areas, or those targeted by the ad campaign. In the high and low saturation condition, the segments exposed to the ads within each municipality were selected randomly.

The main advantage of randomizing ad exposure both across municipalities and across contiguous segments within treated municipalities is that it allows the authors to experimentally identify several different impacts of the campaigns:

- The direct effect of being targeted by the campaign, by comparing election outcomes in treated areas in low and high saturation municipalities (shaded in the figure above) to areas in control municipalities.

- The indirect effects of the campaign, by comparing untreated (unshaded) areas in low and high saturation municipalities to areas in control municipalities.

- How the effects in (1) and (2) differ according to the level of saturation, by comparing treated (shaded) segments in low versus high saturation municipalities as well as untreated (unshaded) segments in these two groups.

The study included 128 municipalities, comprising roughly a quarter of Mexico’s population. Around 15% of voting-age adults in treated segments watched at least 3 seconds of the videos.

Results

On average, the Facebook ads increased vote shares for incumbent parties by 2.6 percentage points in segments directly treated by the informational campaign. This positive relationship is consistent with the fact that many municipalities in the sample saw no financial irregularities in their audits. Given the Mexican public’s pessimistic expectations about the prevalence of corruption, it is likely that the ads caused voters in these municipalities to update positively about the incumbent party’s performance relative to their prior beliefs. To illustrate this point, the authors look at how treatment effects vary by the level of irregularities discovered in each municipality’s audit. This analysis reveals significant heterogeneity: in areas where the ads reported zero or negligible irregularities (less than 0.7% of total expenditures), the campaign increased incumbent party vote shares by 6.1 percentage points, whereas in areas with more significant irregularities, incumbent parties saw a 2.4 percentage point decline in their vote share (although this negative effect is not statistically significant). Overall, then, the ad campaign’s effects seem to have worked largely by informing voters of politicians’ good performance, rather than provoking voters to sanction incumbents with poor performance.

The authors also show that the effects of revealing good performance were significantly larger when the Facebook ad campaigns targeted a greater proportion of voters in a municipality. In areas that were highly saturated with the ads (i.e. 80% of voters targeted), ads reporting minimal irregularities increased the incumbent party’s vote share by 7.9 percentage points in targeted areas relative to the control group. This same effect was significantly lower, at just 2.2 percentage points, in municipalities where 20% of voters were targeted by the ads.

To understand whether the campaign had spillover effects on areas within treated municipalities that were not directly targeted by the ads, the authors compare the untreated areas (i.e. the unshaded segments in panels (B) and (C) in the figure above) to the control municipalities. They find that the indirect effect is nearly as large as the direct effect in municipalities where 80% of the electorate was exposed to the ad campaign. In areas of low saturation, where just 20% of the municipal electorate was targeted with the treatment, the indirect effects are significantly smaller and statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Finally, the authors investigate the theoretical mechanisms driving these substantial effects of non-partisan Facebooks ads. Overall, the large indirect effects of the ads suggest that the information campaign altered voting behavior by more than just persuading those who personally watched the Facebook ads. Instead, the authors show that the ads’ effects were larger in areas with especially dense social networks between voters (measured using Facebook’s Social Connectedness Index). Combined with the finding that treatment effects increased with municipal saturation, this evidence suggests that he impact of the social media intervention was amplified by interactions between citizens discussing and sharing the ads’ information about incumbent performance. It does not appear that the ad campaign triggered strategic messaging by either media outlets or politicians.

Lessons

This study demonstrates that low-cost, non-partisan informational campaigns on social media can meaningfully strengthen electoral accountability. In the Mexican case, the authors estimate that a one percentage point increase in vote share for the best-performing incumbent parties cost $11 USD. For policymakers looking to implement similar accountability-promoting interventions, this study highlights two key factors for success. First, these kinds of ad campaigns are most influential when they simultaneously reach a large proportion of eligible voters, which amplifies the effect of the message beyond social media users. Second, these ads are likely to be especially effective in contexts with dense social networks among voters. These areas are more likely to see voters discuss politics with friends, neighbors and family members, which can facilitate information sharing and tacit vote coordination based on the content of the ads.