Brief 74: Using Media Campaigns to Empower Women Facing Gender-Based Violence

EGAP researchers: Fotini Christia and Horacio Larreguy

Other researchers: Norhan Muhab and Elizabeth Parker-Magyar

Key takeaway: Sending dramatized video content promoting women’s empowerment to women in Egypt can boost respondents’ likelihood to report gender-based violence to supportive organizations, although it may not change their underlying attitudes.

Geographical Region: Middle East and North Africa

Type of study: Randomized encouragement intervention

Preparer: Nick Kuipers

Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the conditions giving rise to gender-based and intimate partner violence. What can policymakers do to empower women to condemn gender-based violence and intimate partner violence? Local organizations may play a crucial role in providing relevant information and resources to victims, with the ultimate goal of undermining the incidence of such events in the first place. But outreach to victims remains difficult since COVID-19 has limited organizations’ ability to implement traditional in-person, often community-based, interventions. The authors of this study partnered with the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights (ECWR) to study the impact of their videos concerning women’s empowerment across television and social media in Egypt.

Comparing outcomes for women who did not receive this content until the evaluation was over, against women who received text messages with links to the content or reminders to watch the television show, the authors find that those in the treatment groups were:

- More likely to have watched the online and television content, and report greater knowledge about resources for victims of gender-based and intimate partner violence;

- More likely to know organizations to contact or resources to access in the event of a hypothetical violent incident, and were more likely to have recently accessed resources from organizations active in stopping gender-based and intimate partner violence;

- However, they were no more likely to hold attitudes condemning the acceptability of gender-based and intimate partner violence, nor were they more likely to donate to an organization supporting survivors.

Policy Challenge

Despite recent advances, the incidence of gender-based violence (GBV) and intimate partner violence (IPV) remains persistently high in many countries. Worryingly, the COVID-19 pandemic, and governments’ resulting stay-at-home orders, has increased women’s exposure to GBV and IPV. Yet widely-held social norms have led to many women believing that violence is justified—a situation that sustains its incidence and discourages women from seeking help when they are victimized. Moreover, COVID-19 has limited organizations’ ability to implement traditional in-person, often community-based, interventions. Empowering women to both condemn the incidence of such forms of violence and encouraging them to seek out support in its aftermath are thus pressing policy concerns.

Context

The authors focus on the Egyptian context—a country with high levels of gender inequality. According to a 2015 survey of Egyptian women, 36% reported having experienced physical domestic violence. Strikingly, only one-third of these women sought help in stopping future such incidents, and only 18% reported the episode. These figures reflect broader social norms surrounding the incidence of gender-based and intimate partner violence: in 2005, more than half of Egyptian women surveyed reported that physical domestic violence was justified in certain hypothetical situations. In turn, there has been a significant increase in the use of the internet and social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research Design

The authors worked with the Egyptian Center for Women’s Rights (ECWR) to craft a series of videos concerning women’s empowerment to be delivered to women across Egypt. These videos featured the activist and founder of the ECWR, Nehad Aboul Qomsan, speaking in a conversational tone directly to the audience, conveying information that seeks to change women’s perceptions of the acceptability of violence. The videos also provided information on legal and other resources for women impacted by violence.

The authors leveraged two different forms of content, both of which featured Nehad Aboul Qomsan speaking directly to the camera. The first set of videos constituted the latest season of a weekly television show, which was a 25-30 minute show aired on Saturday evenings on a satellite network. The second set of videos were shorter 5-9 minute videos intended for social media dissemination.

To evaluate the efficacy of these videos on changing women’s stated acceptance of gender-based and intimate partner violence, as well as their knowledge of available resources, the authors recruited a sample of approximately 6,000 Egyptian women. In addition to a control group, the authors split the remaining respondents into five groups:

- One treatment group received regular WhatsApp messages reminding them about the airing of the TV show.

- Another treatment group received an invitation to join a WhatsApp group in which they were then provided with links to watch the shorter videos.

- A third treatment group received individual WhatsApp messages providing them with the same links to the shorter videos.

- The fourth treatment group received Facebook messages with the links to the shorter videos — however, due to technical difficulties arising during implementation, this group was eventually folded into the third treatment group (which received individual messages via WhatsApp).

- A final control group received all of the links to watch the shorter videos upon completion of an endline survey.

The authors first measured whether the mode of delivery was effective in generating information consumption. Then, they measured whether the information shifted attitudes towards gender-based and intimate partner violence, as well as whether it increased knowledge about resources and support for victims. Finally, they look at whether or not information changed respondents’ hypothetical and reported behavior, as well as their future outlook toward gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Results

The authors show that—for all treatment arms—respondents assigned to one of the treatment interventions reported higher consumption of information concerning women’s empowerment. Respondents who were assigned to the TV treatment were more likely to have watched the TV show, while respondents who were assigned to receive nudges to watch the online video content reported doing so at higher rates. Importantly, for all treatment arms, respondents assigned to watch content report greater knowledge about resources for victims of gender-based and intimate partner violence.

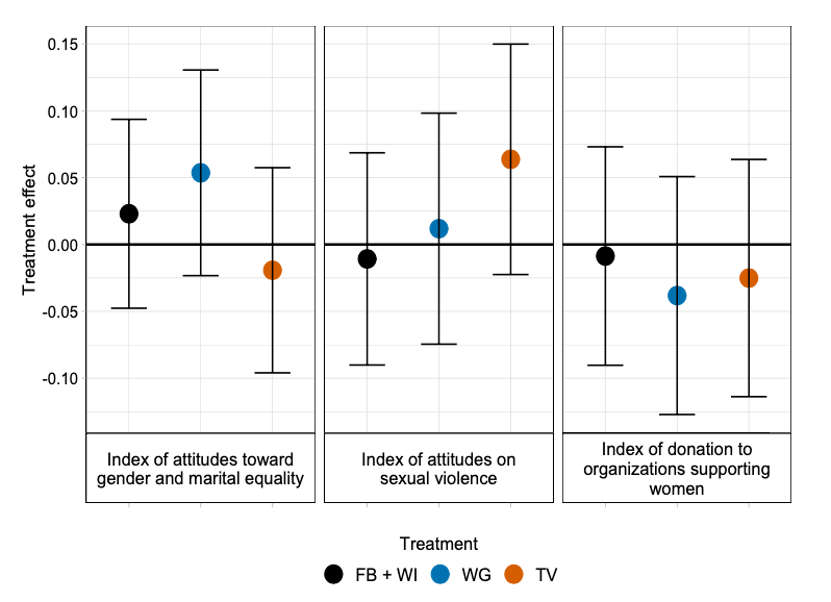

Next, the authors investigate whether those who received a nudge to watch either the online content or the television show were more likely to adopt attitudes more supportive of gender equality and more condemnatory towards sexual violence. The authors find no effect of watching either television or social media content on these attitudes (see Figure 1). Further, the authors quizzed respondents on whether or not they would be interested in donating all or a portion of the monetary incentive they were given to participate in the study to organizations supporting women, finding that those who were assigned to watch content were no more likely to donate than those in the control group.

Figure 1. Changes in attitudes toward gender and marital equality, and sexual violence

WG: Group receiving an invitation to join a WhatsApp group.

TV: Group receiving regular reminders to watch the TV show.

Treatment effect sizes are shown in standard deviations.

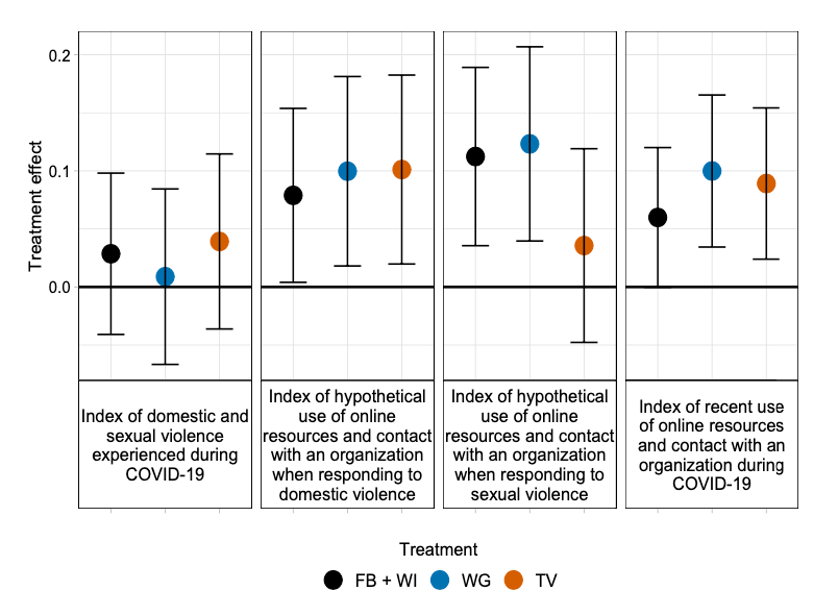

The authors also asked respondents how they would handle hypothetical incidents of gender-based and intimate partner violence as well as their recent use of these resources. As shown in Figure 2, the authors demonstrate that respondents provided with video content are more likely to contact relevant organizations in the event of domestic or sexual violence, when compared to the control group. Extending this insight, the research also indicates that respondents shown the video content were systematically more likely to have actually made use of the resources provided by relevant organizations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, despite the limited impact on attitudes toward gender and marital equality or rejecting violence, those provided with the intervention content via WhatsApp and Facebook directly did express beliefs that women in Egypt would achieve greater gender and marital equality in the future.

Figure 2. Changes in likelihood to use GBV and IPV online resources

WG: Group receiving an invitation to join a WhatsApp group.

TV: Group receiving regular reminders to watch the TV show.

Treatment effect sizes are shown in standard deviations.

Lessons

The authors show—first and foremost—that dramatized interventions can shift the likelihood of individuals to report violence. Yet, the authors find no evidence that these same interventions shift underlying attitudes, suggesting the simple informational impact is decisive. More importantly, the authors show that leveraging social media platforms and television to communicate with women is a cost-effective way of getting critical information to vulnerable populations in a context where organizations face limited ability to implement traditional in-person, often community-based, interventions.