Brief 78: How Can States Consolidate Peace after Civil War? Leveraging Communal Institutions to Reduce Governance Gaps in Rural Colombia

EGAP researchers: Robert Blair

Other researchers: Manuel Moscoso-Rojas, Andrés Vargas Castillo, and Michael Weintraub

Key takeaway: Post-conflict state building is difficult and incremental. States transitioning out of civil war face many challenges that can threaten tenuous peace deals and rebel group demobilization. The authors examine whether partnering with communal institutions can help states consolidate peace and stability following civil war. They find evidence that leveraging the different capacities of the state and communal institutions—that is, their complementarities—can improve local dispute resolution and impede the entry of new rebel groups in abandoned territories.

Geographical Region: Latin America and the Caribbean

Type of study: Field experiment

Preparer: Catlan Reardon

Executive Summary

Many states struggle to consolidate peace and security following civil war. There often exist several challenges to regain control of territory previously held by rebel groups—including poor infrastructure, lack of financial and human capital, and limited citizen trust. Within this context, it is difficult for states with limited territorial control to provide local governance and security. Often, these governance gaps increase the likelihood of local conflict and violence, as well as offer opportunities for new rebel groups to take over territory once held by their rivals.

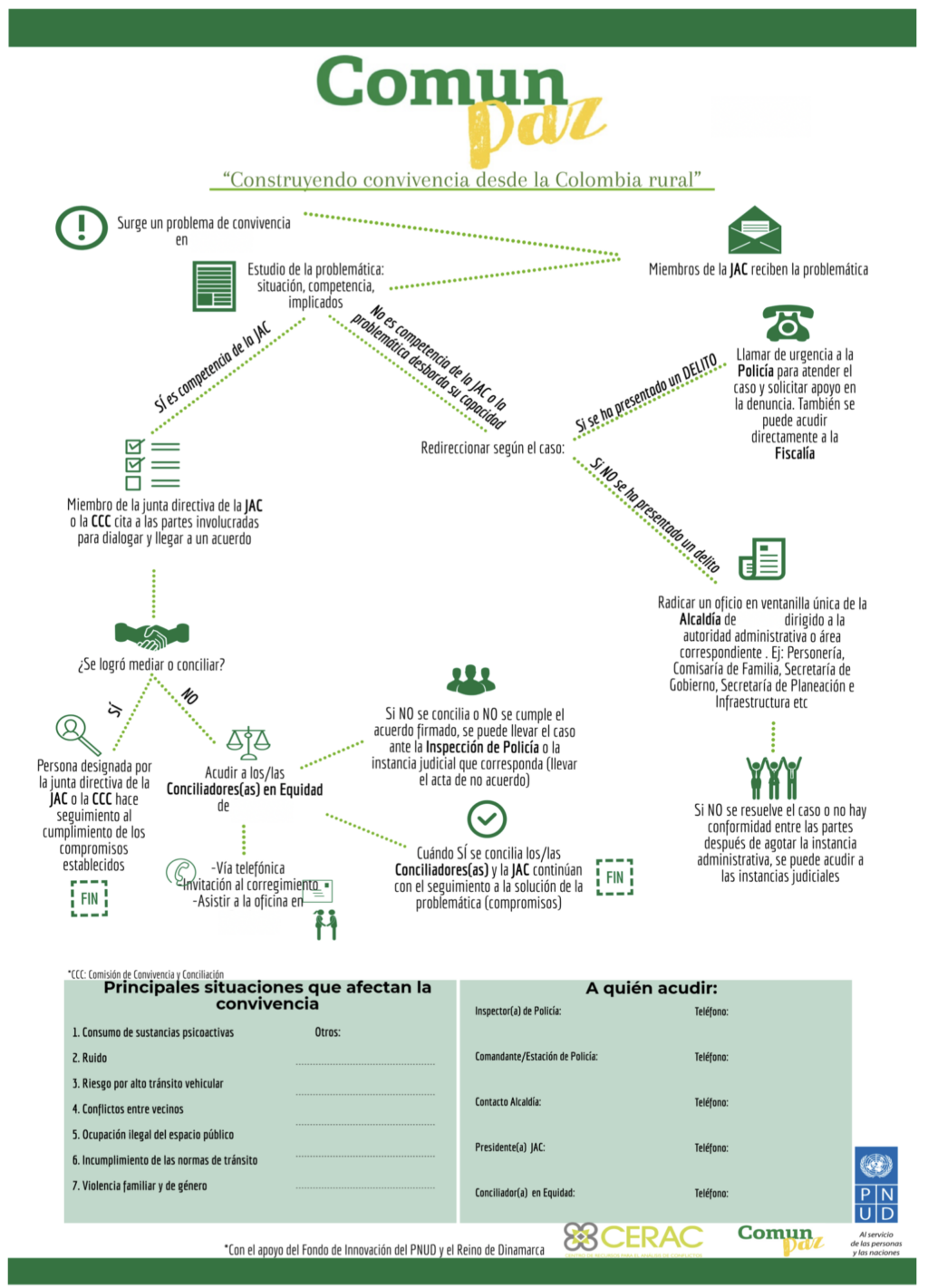

The authors posit that one strategy to manage governance gaps is for the state to partner with communal institutions. Communal institutions possess inside information and local legitimacy, while the state has coercive capacity and material resources. In leveraging these complementarities, states transitioning out of civil war can increase their legitimacy, improve the quality of local dispute resolution, and prevent the resurgence of new or existing rebel groups in areas recently abandoned by prior rebel groups. To test their core hypotheses, the authors conducted a field experiment in Colombia evaluating the effect of the ComunPaz program, an inexpensive, scalable intervention designed to exploit the complementarities between communal institutions and the state. The program was implemented following the demobilization of Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), Colombia’s largest rebel group.

The authors find that the ComunPaz program reduced the quantity of unresolved and violent disputes, with somewhat more suggestive evidence that citizens lessened their reliance on armed groups and diminished their trust in armed groups as well. They also find that the program increased coordination and trust between communal institutions and the state, while also improving the functionality of communal institutions themselves. Contrary to expectations, the authors find no evidence that the program improved citizens’ perceptions of communal institutions or their understanding of the responsibilities of communal authorities under Colombian law. Relatedly, the authors do not find any shifts in demand for more coordination between the state and local institutions. Furthermore, the intervention did not increase awareness among either the state or communal institutions of the most serious disputes in the community or how they should be resolved. Lastly, the authors do not find any uptick in reliance on state or communal leaders in dispute resolution. One possible explanation is that the ComunPaz program improved cohesion and lessened conflict among residents, obviating the need for external dispute resolution. The study offers important insights into how states promote peace and security in the wake of civil war.

Policy Challenge

Civil war and conflict destabilize and weaken the state’s ability to govern and provide local security. Peace agreements and rebel group demobilization occur within a tenuous and uncertain security environment. Citizen trust in the government is limited and competing rebel groups often vie for control of previously held territory. In this context, states face significant risks that local level disputes and conflicts may escalate into larger forms of violence, threatening national peace and stability. This study offers evidence into how states can manage the transition out of civil war such that the likelihood of a return to rebel governance and conflict is reduced.

Context

The study was conducted across four regions in Colombia following a peace agreement with FARC, Colombia’s largest rebel group. The conflict between the government and FARC lasted for over 50 years with significant human and financial costs. The government has faced many challenges during the post-conflict transition, including reestablishing authority in rural areas, preventing local conflict, and inhibiting the entry of new rebel groups into FARC-controlled communities. The ComunPaz program is one attempt at smoothing the transition to peace. The program targets three important actors in conflict resolution: police officers, Police Inspectors, and Juntas de Acción Comunal (JACs). JACs retain independence from the state and are tasked with providing local public goods and resolving local disputes. Generally, JACs are composed of one representative from each household in a community (Vargas Castillo 2019).

Research Design

The authors conducted a field experiment to examine whether exploiting complementarities between the state and communal institutions can prevent rebel resurgence and improve local conflict resolution. The field experiment was implemented in 149 communities across 24 municipalities in rural Colombia between October 2018 and May 2019. Importantly for the study’s theoretical predictions, the evaluation occurred following the demobilization of FARC, but before rival armed groups could solidify strong territorial or governing control. Municipalities were selected purposefully from four regions of Colombia with a history of FARC presence, excluding those with ongoing violence or extremely difficult terrain. The authors targeted rural communities with fewer than 5,000 residents—both to reduce cluster size heterogeneity and given the rural focus of the intervention design. The intervention was then randomly assigned to 72 communities in the sample stratified by region and blocked by population.

The intervention, called the ComunPaz program, broadly aimed to inform the state and communal institutions of the legal roles of their respective counterparts, increase trust between relevant actors, and increase coordination between the state, communal institutions, and citizens. The program was implemented by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the Colombian government’s National Planning Department (DNP), and the Conflict Analysis Resource Center (CERAC). Specifically, the ComunPaz program targeted police officers, Police Inspectors, and the JACs. The program—delivered via lectures, discussions, group work, and Q&As—included four modules lasting four days, implemented over the course of three months. The authors draw from several data sources to measure their core outcomes. First, they conducted an endline survey roughly seven months after the program. The survey included approximately 18 randomly selected residents and eight purposely selected leaders in each community of the sample. The survey included both endorsement and list experiments to measure citizen support for armed groups and citizen use of armed groups for dispute resolution, respectively. They supplemented these quantitative survey measures with two costly behavioral measures aimed at operationalizing both demand for and actual coordination between police officers, Police Inspectors, and JACs. In addition, one police commander and one Police Inspector in each municipality was surveyed. Last, they triangulated these quantitative measures with detailed qualitative data drawn from field reports compiled by ComunPaz facilitators.

Results

The authors find several results to support their theory that states can facilitate peace and security by collaborating with communal institutions. First, they find that the ComunPaz program decreased the number of unresolved and violent disputes at the community level. Leaders in the treatment group were 9.3 percentage points less likely to report an unresolved dispute and 5.1 percentage points less likely to report a violent dispute in their community. Treatment group residents also reported fewer unresolved and violent disputes than those in the control group, though this result is insignificant at conventional levels. The authors, then, asked respondents to whom they report disputes and who should be responsible for dispute resolution. Residents in the treatment group were 5.6 percentage points less likely to cite that they relied on armed groups for dispute resolution, while there is no effect among leaders. Importantly, among respondents, reliance on armed groups was rare, suggesting that rebel governance at the time of the endline was already quite weak.

Next, the authors do not find any evidence that the ComunPaz program increased understanding among leaders of Colombian law or which disputes residents deemed most serious. They do find, however, improved perceptions of police officers and Police Inspectors—driven primarily by perceptions of Police Inspectors. They also find more negative perceptions of armed groups among residents in the treatment communities, but not among leaders. Interestingly, the evidence does not show that the program improved perceptions of the JACs among residents, but did shift perceptions positively among Police Inspectors. Police Inspectors within the treatment group were 18.7 percentage points more likely to report that they trust JACs compared to those in the control group. While the program did not decrease support for policies endorsed by armed groups, the treatment group respondents were more likely to support policies endorsed by the JACs (weakly significant at the 0.01 level). The low overall level of support for armed groups could explain the null effect of the armed group endorsement.

The evidence demonstrates some improvements in coordination between the state and the JACs. Drawn from the leader survey, the authors find that the effect on coordination is driven by Police Inspectors in the sample, with a 24.9 percentage point increase in coordination among Police Inspectors. Similar to previous results, the authors hypothesize that the strong effect among Police Inspectors stems from them interacting more with community members than police officers. In addition, there is some evidence that trust within the JACs was improved by the program. Members of JACs in treatment communities were 15.3 percentage points more likely to answer positively to outcomes measuring trust and coordination with co-JAC members. The behavioral outcomes yield interesting results. Residents in the ComunPaz program were actually less likely to sign a petition asking for more coordination between the state and the JACs, but these analyses suffer from missing data. The authors posit that this result may stem from the fact that the program already satisfied the demand for coordination among citizens.

Lessons

Overall, the results demonstrate the importance of bridging the gap between the state and communal institutions in the aftermath of civil war. Leveraging the complementarities between the state and local institutions can help alleviate three obstacles common in postconflict settings: a lack of (1) information, (2) trust, and (3) coordination. The ComunPaz program sought to overcome these challenges targeting police officers, Police Inspectors, and citizens in Colombia. Arjona (2016) describes how armed groups often co-opt communal institutions to assist in rebel governance. The authors posit a similar strategy—between the state and communal institutions—that can enable states to consolidate peace and improve local governance during transitions out of civil war.