Brief 76: Community Policing in Liberia Increased Reporting and Lowered Crime

EGAP researchers: Robert Blair and Sabrina Karim

Other researchers: Benjamin Morse

Key takeaway: Recurring “confidence patrols” by newly-retrained, better-equipped police officers can reduce some types of crime, strengthen property rights, and improve citizens’ understanding of the criminal justice system, even in a weak and war-torn state, but may not improve citizens’ trust in the security apparatus.

Geographical Region: Africa

Type of study: Randomized experiment

Preparer: Nick Kuipers

Executive Summary

How can policymakers increase citizens’ trust and cooperation with the police? Working with the Liberian National Police, the authors of this study evaluate the efficacy of an initiative that deployed newly-retrained, better-equipped officers for recurring “confidence patrols” to rural communities. During the patrols, officers would hold town hall meetings, conduct door-to-door foot patrols, distribute informational posters, and play soccer with local youths. The authors find several salutary effects of the initiative in communities that received these patrols. Specifically, they find that citizens in communities in the treatment group:

- Reported fewer instances of felonies such as domestic violence and assaults;

- Were more likely to understand the criminal justice system and Liberian law; and

- More likely to feel secure in their property rights and less likely to report land disputes, one of the most important sources of violence in rural Liberia.

However, citizens in these communities were no more likely to report that they trusted the police or the courts, nor were they more likely to trust the government more generally.

Policy Challenge

Particularly in post-conflict settings, governments frequently struggle to provide security to their citizens, who are often wary of the state security apparatus. Citizens in these contexts may be unaware of their legal rights, and where to go to report a crime or solicit police services. But police training and infrastructure may also be part of the problem, as officers are inexperienced in engaging in routine contact with citizens and they sometimes lack the morale to engage in these activities due to a lack of resources. In these contexts, informal institutions often arise to fill citizens’ needs for security and dispute resolution. These institutions can be quick and effective, but they can also exacerbate forum shopping and undermine the credibility of the police. Restoring police-community relations is thus an important policy concern for governments in post-conflict settings interested in reasserting legitimacy.

Context

The authors focus on the Liberian context—a country that suffered a devastating civil war from 1989-2003. Insecurity is widespread in Liberia, yet citizens rarely avail themselves of police services. According to a 2009 survey, only 2% of victims reported crimes to the police, with 59% of incidents not being reported at all. Informal institutions fill the gap, with 38% of cases being reported to such bodies, which, in the Liberian context, include chiefs, councils of elders, and customary institutions known as “secret societies.” Unfortunately, however, conflict resolution in these institutions is often biased against women, ethnic minorities, and those without connections to local political power.

Research Design

The authors worked with the Liberian National Police (LNP) to evaluate what are known as “confidence patrols,” in which teams of 10-12 officers are deployed to recurring visits to towns in rural Liberia. These teams are comprised of members of an elite unit of better trained and better equipped officers within the LNP. Officers participating in the confidence patrols also received an additional day-long training course on community policing, which covered topics such as proactive policing, the importance of citizen trust, and the responsibilities of officers, local leaders, and citizens.

During the confidence patrols, officers would hold town hall meetings, in which anywhere from 15 to 125 citizens would attend. Officers delivered two presentations to the attendees, the first of which provided information to citizens on how to access police services and the second of which conveyed information on the roles and responsibilities of the LNP. Officers also conducted foot patrols to speak with citizens and solicit concerns in private settings, distributed informational posters, and played soccer with local youths. The patrols often lasted multiple hours, and officers sometimes spent the night in the villages they patrolled. Most communities were visited four or five times by confidence patrols during the 14 months of the program.

To evaluate the efficacy of these confidence patrols on citizens’ trust and cooperation with the police, the authors identified 74 communities in rural Liberia. The authors then randomly assigned 36 of these communities to receive confidence patrols in a manner that ensured an adequate geographic dispersion of the communities receiving visits. In each community, the authors surveyed 18 adult citizens and 5 local leaders, probing outcomes including knowledge of the law, perceptions of government institutions, and crime victimization. The authors also draw on administrative police data capturing crimes reported to the police.

Results

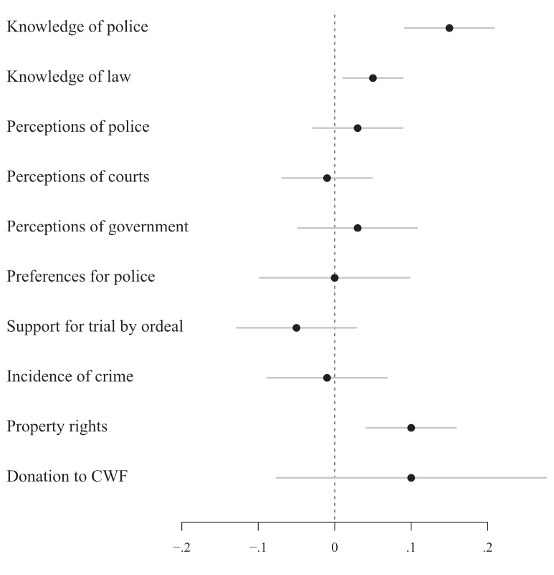

The authors show that, in communities assigned to receive confidence patrols, citizens reported a greater knowledge of the police and a better understanding of Liberian law, compared to communities that did not receive patrols. Misunderstanding of the criminal justice system is often an important barrier to crime reporting in post-conflict settings, especially in rural areas, where many citizens do not know how to access the police or courts, and may not know which offenses do and do not qualify as crimes under the law. However, citizens in confidence patrol communities were no more likely than their unpatrolled counterparts to report greater trust in the police, courts, or other government institutions. Citizens in treated communities were also no more likely to state a preference for the police over informal institutions in the event they were the victim of a hypothetical crime.

Yet, citizens in communities assigned to receive confidence patrols reported a significant improvement in their perceived security of property rights. This is an important issue in rural Liberia, where the escalation of land disputes is a frequent cause of violence. Citizens in confidence patrols communities were also more likely to donate money to community watch forums (CWFs), though this effect was not statistically distinguishable from zero.

Importantly, the authors find that confidence patrols decreased the likelihood that citizens would let crimes go unreported by 4 percentage points, an effect that was driven entirely by an increased likelihood of reporting crimes to the police rather than informal institutions. This uptick in reporting is most pronounced for felonies, rather than misdemeanors. Specifically, citizens in communities receiving confidence patrols were 16 percentage points more likely to report a felony than those in communities that received no confidence patrols.

Overall, the authors find that citizens in communities receiving confidence patrols reported no less crime than those in unvisited communities. However, this finding obscures important differences in the efficacy of confidence patrols for different types of crimes. Specifically, the authors find that citizens in communities receiving confidence patrols were significantly less likely to report domestic violence or simple assault; they report no such effects for aggravated assault, armed robbery, burglary, or rape.

Lessons

The authors show that, in post-conflict settings, training and equipping police to engage in town hall meetings and foot patrols can strengthen property rights, improve citizens’ understanding of the criminal justice system, boost their willingness to report crimes to the police, and reduce the incidence of some serious crimes. Yet, this intervention appears to have no impact on citizens’ underlying levels of trust in the police, courts, or government, suggesting that its effects may operate mostly by boosting citizens’ knowledge of the law. Importantly, these interventions appear scalable, as officers only received a single-day training yet made a substantively meaningful impact on citizen safety and security.