Brief 70: How Personal Narratives Reduce Negative Attitudes Towards Immigrants in Kenya

EGAP researchers: Kristin Michelitch

Other authors: Nicole Audette and Jeremy Horowitz

Geographical region: Africa

Research question: Do personal narratives reduce prejudicial attitudes towards immigrant outgroups and policies aimed at benefiting them?

Preparer: Bhumi Purohit

Executive Summary

Do personal narratives reduce prejudicial attitudes towards immigrant outgroups and policies aimed at benefiting them? To answer this question, researchers ran an experiment in Nairobi, Kenya, by presenting Kenyan nationals with one of two personal narratives recorded by Somali refugees and longer-term Somali citizens of Kenya (or no narrative). One narrative focused on the hardships of being a refugee while the other focused on solidarity against terrorism in Kenya between ethnic Somali Kenyans and Kenyans of other ethnicity.

Though Kenyan nationals tend to hold negative perceptions of Somalis despite having little direct contact with them, this experiment showed that personalized narratives can reduce bias. Both narratives reduced prejudicial attitudes towards Somali refugees and citizens and also increased support for beneficial policies. Further, the intervention had effects that were as large or larger among those negatively predisposed towards Somalis.

Personalized narratives such as the ones tested in this study provide a low-cost, light-touch intervention for policymakers. They are adaptable through “edutainment” interventions via radio or television. In a field where there have been few effective interventions found to mitigate bias against immigrant outgroups, personal narratives offer a potentially promising way to mitigate negative perceptions, which may inhibit assimilation in host societies.

Policy Challenge

Anti-immigrant sentiment has increased in recent years, particularly in the Global South which hosts 80% of the world’s refugees. Such attitudes are rooted in misperceptions about the size of the population of refugees in host countries, their behaviors, or the cost of providing government services. Yet, because nationals rarely have contact with refugees, misperceptions are fueled by misinformation in the media, news, and other outlets.

Research shows that negative attitudes about other ethnic groups are particularly difficult to change. Individuals who hold prejudicial beliefs tend to dismiss facts or new information that runs counter to their beliefs. Fact-based interventions therefore have not shown much promise in rigorous tests, especially with regards to impacting policy attitudes. Intergroup contact interventions also reveal few successes, and are extremely expensive and difficult to scale up, especially among those negatively predisposed towards immigrants. Perspective-taking exercises have also shown mixed results, and also may be difficult to implement among those predisposed against immigrants. Yet, one technique that is used by immigration advocacy groups – personal narratives – has not been tested. The authors test this intervention and find that it leads to significant reduction in prejudicial attitudes towards Somalis in Kenya.

Local Challenge

Kenya, where this intervention takes place, holds one of the world’s largest refugee populations. Due to violence, state collapse, and intermittent droughts in Somalia since the late-1980s, hundreds of thousands of Somalis have sought refuge in neighboring countries, now making up the majority of Kenya’s half-a-million refugee population. Somalis generally have little contact with Kenyan nationals, and are often perceived negatively amongst the general population. Recent violence in Kenya led by the Somali-based Islamist terrorist group, Al Shabaab, has led to the media portraying Somalis as a national security threat, leading to further discrimination, police brutality, and marginalization by government officials.

Research Design

To create the intervention, the authors worked with leaders from Eastleighwood, an advocacy organization based in Nairobi that creates video content to connect Somalis and non-Somali Kenyans. Following interviews and meetings with the Somali community in Nairobi to assess their personal experiences, they created two audio recordings that reflect common experiences and sentiments.

The first narrative was inspired by Somali refugees and focused on refugee hardship. The speaker narrates his family’s migration to Kenya due to hardship in Somalia, discusses life in the refugee camps, and thanks the Kenyan government for providing safe haven.

The second narrative was inspired by long-standing Kenyan citizens of Somali descent and focused on anti-terror solidarity. The speaker discusses his identity as a Kenyan Somali and how this identity supersedes the religious divide between Somali Muslims and Christian Kenyans. The speaker then expresses solidarity with Kenyan nationals against Al Shabaab and terrorism.

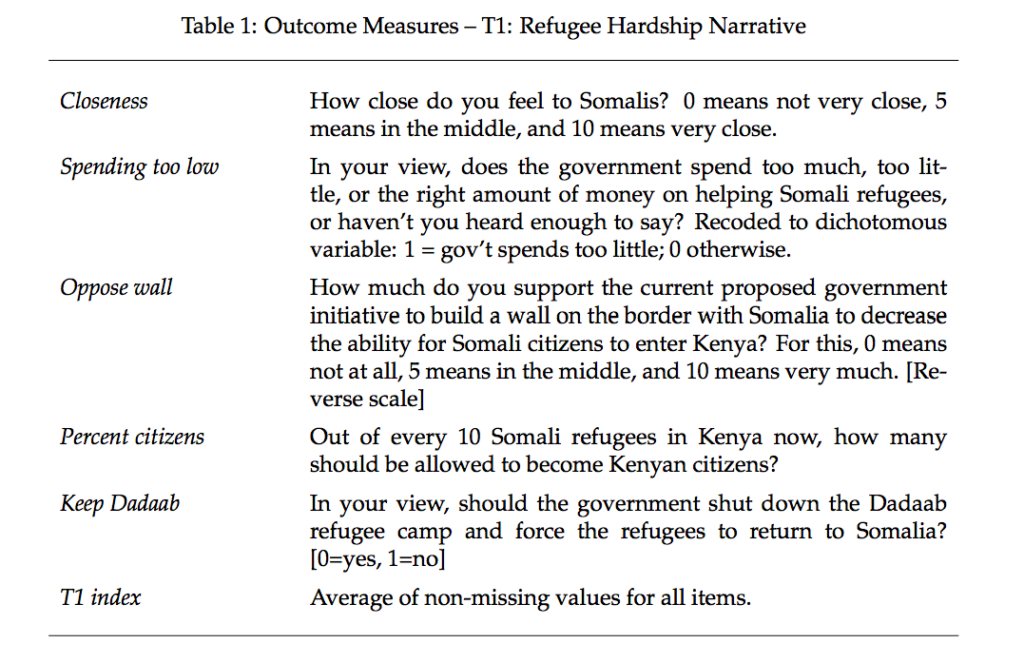

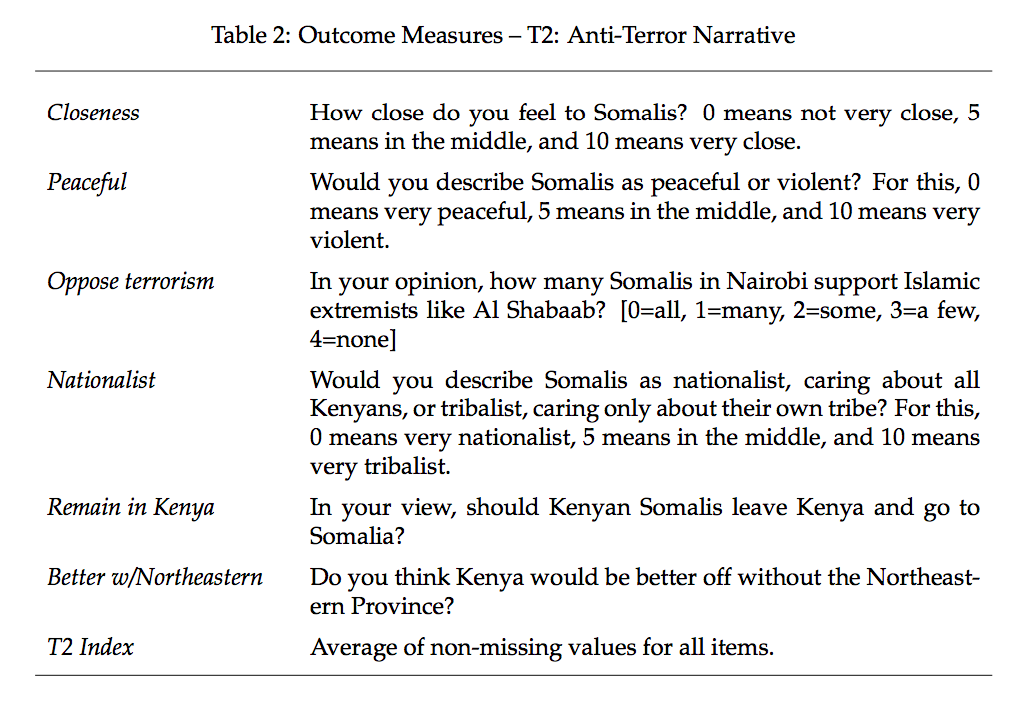

These narratives are tested amongst a representative sample of 1,112 non-Somali Kenyans in Nairobi who are randomly assigned to listen to no recording (control) or one of the recordings (treatment 1 and treatment 2). The outcomes measured for treatment 1 and treatment 2 are listed in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Results

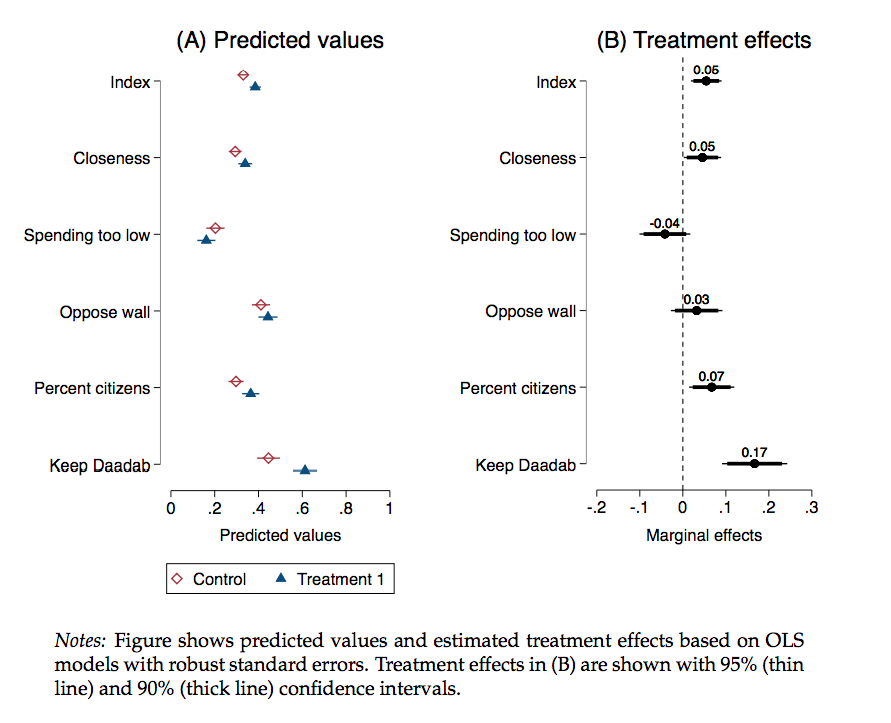

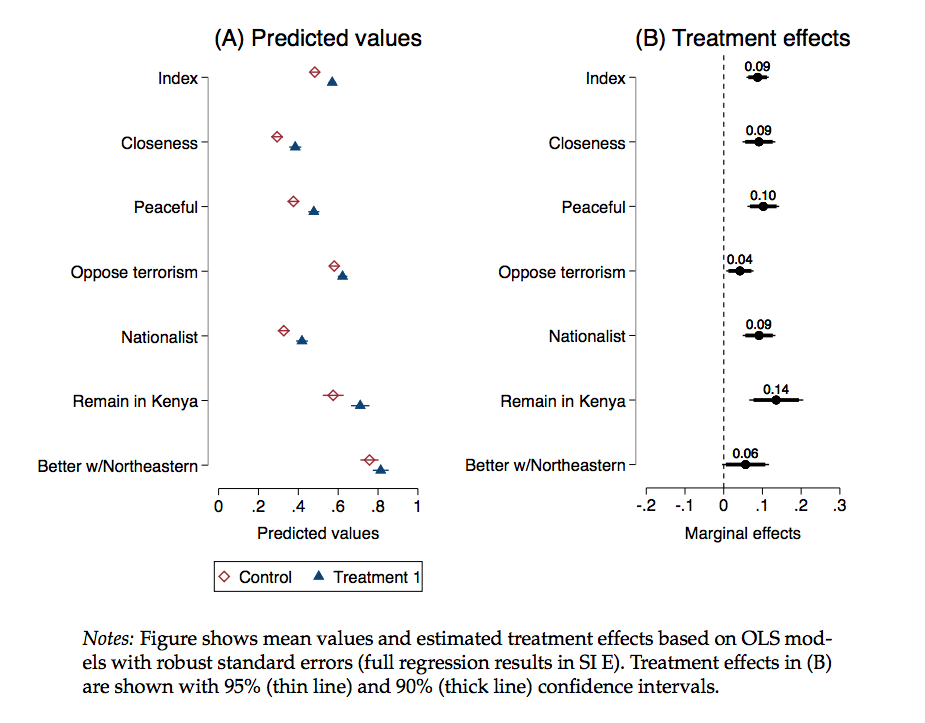

To compare overall change in attitudes, the authors create an index of all variables in Table 1 and Table 2. Compared to the control group, both treatments have a positive and statistically significant effect on reducing prejudicial attitudes and increasing support for pro-Somali policies.

Listening to the refuge hardship recording increases respondents’ feeling of closeness to Somalis by 5 percentage points. It also increases support for policies directly related to the narrative’s content — such as allowing Somalis to become citizens (increase of 7 percentage points) and keeping the Dabaab refugee camp open (17 percentage points). However, there is no significant change in other policies that are less related to the narrative content, such as government spending for Somali refugees or building a border wall, as seen in Figure 1.

Listening to the anti-terror solidarity recording increases respondents’ feeling of closeness to Somalis (by 9 percentage points) and positively affects a range of other perceptions and policy preferences, as seen in Figure 2.[1] Most importantly, the narrative increases the acceptance of Kenyan citizens of Somali descent (by 14 percentage points, rather than ousting them voluntarily or forcibly to Somalia).

One possibility is that these changes are seen amongst those who already had favorable or moderate views towards Somalis. The authors conduct additional tests and show that in fact, the narratives generally produce as large or larger positive effects amongst those with more negative baseline views. In other words, the narratives change attitudes amongst those with negative pre-existing attitudes rather than merely “preaching to the choir.”

Lessons

Personal narratives may be a scalable, low-cost solution to countering opposition to immigrants and refugees. Scaling up the use of immigrant outgroups’ personal narratives through radio, TV, and other educational entertainment mediums may reduce divides between communities, improve support for refugees or other immigrant outgroup members, and change policy attitudes. Further work needs to be conducted to understand how long these effects last and whether they obtain in other contexts. Further, future research might seek to compare exposure to personal narratives to other strategies used by advocacy and policy groups, which tend to show limited or mixed results and which can be more expensive and less scalable (e.g., face-to-face canvassing, perspective-taking exercises, and presenting factual information).

Watch the Policy Brief Webinar presentation by Kristin Michelitch and Jeremy Horowitz (October 29, 2020)

[1] While almost all outcome variables are significant at p<0.5 for the anti-terror solidarity treatment, the variable for keeping Northwestern Province in Kenya is significant at p<0.1.