Brief 68: How politicizing an epidemic can shape public attitudes on immigration: Evidence from Ebola in the US

EGAP Researcher: Claire Adida, Kim Yi Dionne, Melina Platas

Geographical region: North America

Research question: How do threats to public health and the politicization of these threats affect attitudes towards immigration in the United States?

Preparer: Tanu Kumar

Background

In August 2014, two Americans assisting with the Ebola outbreak response in Liberia became infected themselves and were evacuated to the United States. The next month, a Liberian national infected with Ebola arrived and was hospitalized in Dallas, Texas; shortly after, two nurses in the same hospital became the first people to contract Ebola in the United States.

As the November 2014 midterm elections approached, the American media began to cover the Ebola epidemic around the clock. Ebola was often portrayed as a disease associated with Africans and African practices, and African immigrants in Dallas also began to experience prejudice and stigma.

At the same time, several American politicians, particularly Republicans, began to propose travel bans as an effective response strategy to the disease. There was a range in the sensationalism of this rhetoric, but it overwhelmingly targeted non-citizens and suggested that they were responsible for bringing the disease to American soil.

By September 2014, over 1/3 of Americans were concerned that there would be a large Ebola outbreak in the United States. Public opinion polls from the last quarter of 2014 found partisan differences in the appropriate response to this threat. While 65% of Americans wanted to bar entry to those who had recently been in Ebola-affected countries, Republicans (78%) held this view at a much higher rate than Democrats (57%).

Research Design

To understand the extent to which public health crises and their surrounding political rhetoric affect attitudes towards immigration, the authors conducted an online survey experiment among a national sample of 3,881 US residents between November and December 2014. The experiment was run through Qualtrics with respondents recruited by Survey Sampling International. Because of the Ebola cases and anti-immigrant sentiment reported in and around Dallas, Texas, about 40 percent of the sample was recruited from Texas.

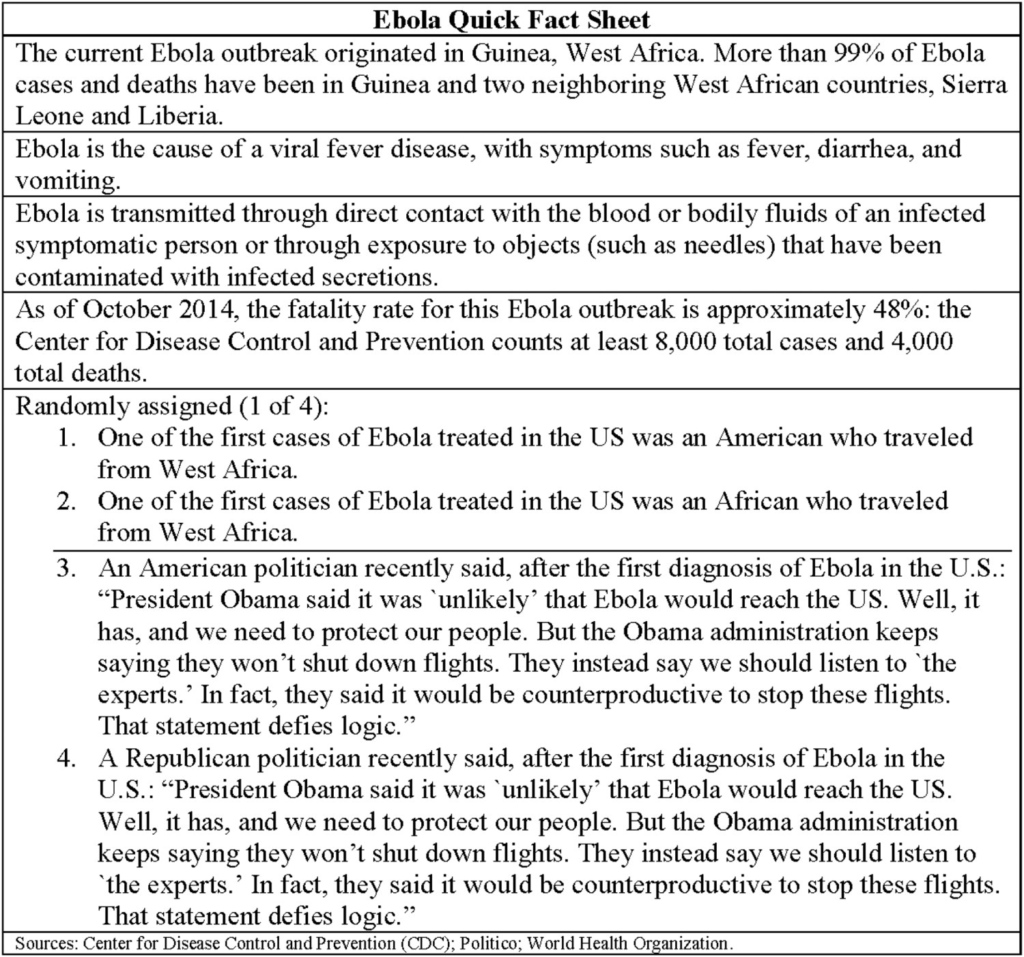

After completing a section collecting pre-treatment covariates, survey respondents were exposed to one of five versions of the survey. Two-thirds of the sample (n=2564) was randomly selected to see a factsheet on Ebola (Figure 1) before answering questions about their immigration preferences, while the remaining third saw the fact sheet after expressing their immigration preferences . Among the treated sample (the one reading the factsheet first), respondents were randomly assigned to four different versions of the factsheet. Its first four facts were equivalent in all versions, but the last fact was unique to each treatment version, as in Figure 1 and specified below:

1) American carrier (n=612): information on the American origin of one of the first cases of Ebola in the US

2) African carrier (n=655): information on the African origin of one of the first cases of Ebola in the US

3) American politician (n=653): a quotation by a politician, described as an “American politician,” criticizing Obama’s response to the Ebola crisis

4) Republican politician (n=654): a quotation by a politician, described as a “Republican politician,” criticizing Obama’s response to the Ebola crisis

Results

The main outcome of interest was an index built using responses to three questions frequently used to measure attitudes toward immigrants in the US:

- Which of these two views comes closer to your own views: Immigrants today strengthen our country because of their hard work and talents/Immigrants today are a burden on our country because they take our jobs, housing, and healthcare?

- Do you believe legal immigration levels should be: Decreased/Kept the same/Increased?

- Do you believe that illegal immigrants already here should be: Allowed to stay permanently/Granted temporary worker status/Required to return home?

The authors found no effects of reading the factsheet in general on attitudes toward immigration relative to the control group. Relative to the control group, respondents receiving the American carrier or African carrier factsheets had more positive evaluations of immigrants, though this rarely reached conventional levels of statistical significance. The authors cite three possible explanations for the small but positive effect here. First, objectively stated facts about the crisis may have tempered fears and biases about the disease. Second, reading about an actual victim may have elicited feelings of empathy that spilled over into attitudes towards immigration. Finally, the factsheet could have triggered social desirability bias, thereby eliciting artificial positive attitudes towards immigration.

However, politicizing the epidemic did shape immigration attitudes for the worse. Reading a politician’s statement critical of President Obama’s response had a negative effect on immigration attitudes for both Republican and Independent respondents. And when the politician was identified as a Republican politician, the effect increases in size and statistical significance for Republican respondents: while just under 40% of Republicans in the control condition claimed that immigrants in the United States strengthen the country, this estimate dropped to 32% for Republicans in the Republican politician condition.

Policy Implications

The subgroup effects for the Republican politician demonstrate that political rhetoric around disease can shape attitudes towards immigration, even when immigrants are not explicitly mentioned in relationship to the disease. Additionally, that the effects appear among Republican respondents but also among Independents suggests that such politicization can have wide-ranging effects. The results suggest that political elites can manipulate public opinion on immigration by politicizing an implicitly associated issue, namely public health. The study raises important concerns about how political rhetoric about disease can have consequences for vulnerable populations.