Brief 01: Female Voting Behavior in Pakistan

EGAP Researcher: Ghazala Mansuri

Other authors: Xavier Giné

Partners: Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF), Marvi Rural Development Organization (MRDO), Research Consultants, ECI, World Bank

Geographical region: Asia

Research question:

What are the reasons for low rates of political participation among women in rural Pakistan?

Is it possible to encourage higher participation and have a meaningful effect on women’s voting behavior simply by providing them with basic information about the process and importance of voting? If such information is provided to women, do they pass it on to their peers? Are there knock on effects?

Focusing on the 2008 national election in Pakistan, Giné and Mansuri explore the effects of a non-partisan, door-to-door information campaign targeting female voters in rural areas in the southern province of Sindh. They find strong effects of the campaign upon female turnout, independence of candidate choice, and knowledge and perceptions of the democratic process among women that were directly exposed to the program. Furthermore, the effects they find spread, with comparable increases in turnout rates for women who are close friends and neighbors of women who took part in the campaign.

Background

Women in rural Pakistan face many gender-specific barriers to political participation including patriarchal norms that pose constraints on mobility and otherwise limit freedoms at the level of the household as well as the village. Women also face security risks going to the polls: in the lead-up to the 2013 elections, militant groups issued pamphlets declaring voting as un-Islamic for women and groups of village elders issued explicit bans on female voting in some constituencies. Relatively low levels of education and labor force participation among women may also lead to weak motivation to engage with the political process. In the most recent election, 500 out of nearly 90,000 polling stations registered no female votes.

Baseline data collected in the study area indicates large gender differentials in access to media, knowledge of current events and participation in public life. Women in the sample are significantly less likely than their spouses to be able to correctly identify political party signs and names. With high barriers to participation compounding effects arising from a simple lack of awareness, the Pakistani context poses a “hard case” for an information-based campaign to significantly affect female voter behavior.

Research Design

For this study an informational campaign was delivered to women in a sample of villages two weeks prior to the 2008 national election in Pakistan with randomization at the level of within-village geographical clusters.

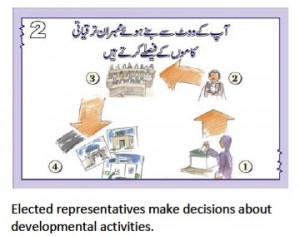

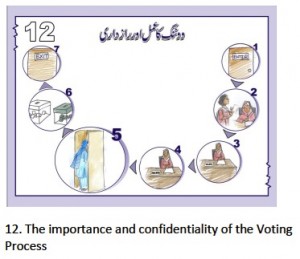

The campaign had two parts: the first provides information about the responsibilities of elected officials, highlights the qualities of a “good representative” and stresses the responsibility of voting to bring about a difference in policies; the second provides additional information about ballot secrecy and confidentiality of the vote. 30 clusters were assigned to receive the first part of the campaign, 27 were assigned to receive both parts and 10 control clusters did not receive either.

Among the 67 clusters assigned to treatments status, a random sample of households received the information, which was delivered by enumerators, exclusively to the women in the household, using visual aids. Randomizing exactly who received the treatment within a cluster allows the researchers to estimate the indirect effects of the campaign upon women who did not directly receive the treatment but are likely to regularly interact with those who did.

Findings

The authors find strong effects of the treatment upon turnout, independence of candidate choice and procedural knowledge.

Turnout is measured using self-reports of voting and also verified using the indelible ink mark placed on voters’ thumbs at the time of voting. The authors also collect administrative data from polling stations to show that treating 10 women increases female turnout by about 9 additional votes.

In the follow-up survey after the election, male household heads were asked about their own candidate choice in the election and that of the women in their household. Women in the households were independently asked about their own candidate choice and that of the other women in their household.

Using these reports, the authors find that treated women are more likely to vote for a different party than the one selected by the male head of household. This is complemented by the finding that treated women (and their friends and neighbors) are more likely to vote for the party with the second highest vote count, rather than the winning party. What’s more, men in treated households are less able to accurately predict which candidates their wives voted for. These effects suggest that women feel more empowered to choose independently.

Policy Implications

Evidence of such large impacts from an informational campaign are reason for optimism about the scope for gains in female political participation even in settings where cultural norms and security threats are thought to fundamentally constrain participation. The strong effects on women’s candidate choice suggests that a targeted informational campaign implemented at a larger scale could actually change party vote shares in a consequential way, with possible implications for the government’s policy agenda and the electoral strategies of parties.