Brief 27: ICT and Politicians in Uganda

EGAP Researcher: Guy Grossman, Macartan Humphreys

Other Authors: Gabriella Sacramone-Lutz

Partners: NDI

Geographical Region: Africa

Research Question:

How does access to information communication technology (ICT) affect who gets heard and what gets communicated to politicians?

Preparer: Gabriella Sacramone Lutz

Recommendations:

A set of experimental subjects randomly sampled from across Uganda was given access to a system that they could use to send a SMS message to their representative in Parliament. These subjects were then randomly assigned to three price groups, (a) Full price (100 shillings), (b) Partial subsidy (50 shillings), and (c) Full subsidy (free). By design, there were an equal number of subjects in each price condition within each parliamentary constituency. In total, 3,790 subjects from nearly a thousand villages participated in the experiment.

Background:

There is growing interest in understanding how technological innovations can change politics. We know that marginalized groups face high barriers to communicating with their political representatives. Can mobile technology help? There are obvious reasons why it could, but there are also fears that ICT will only better connect those that are already well connected. And to date there is little evidence on whether ICTs will exacerbate or reduce communication inequalities. Grossman, Humphreys, and Sacramone-Lutz designed an experiment to find out.

Research Design:

The experiment aimed to test hypotheses regarding underlying demand for mobile-based communication with one’s representatives in Parliament in Uganda, as well as the price effect on demand, and how both demand and price effects vary across social groups.

The first concern is with “flattening,” the extent to which ICT can increase communication from marginalized groups such that their interests are voiced to the same extent as those of traditionally engaged groups. The authors test for two types of flattening—an increase in the volume of communication from marginalized groups, and an increase in the representativeness of communication.

The second question is the effect of price on the use of ICTs for political communication. If messaging is a normal good, lowering the cost of messaging should increase the volume of communication. But this effect may vary across social groups—lacking access to more traditional channels of political communication, marginalized populations may be willing to pay more. Moreover it is theoretically possible that some people will communicate more when the price is high, for example if they think they will have a more exclusive line of communication.

Third, the content of political messaging may be driven by price. For example, expectations of how many other people are likely to be communicating might lead to shifts in the types of requests sent to politicians. If prices are high and few people are messaging then the probability of receiving a private good is higher. Conversely, if messaging is inexpensive, and more people are messaging, then public goods may be a more likely outcome of politician effort when facing demands from many constituents.

Results:

About 4.5 percent of respondents decided to send messages to their MPs. This rate might seem low at first, but it is in fact comparable to other types of political participation outside of election periods in Uganda. If implemented at scale, this rate would yield around a million messages from Ugandans to their Parliamentarians.

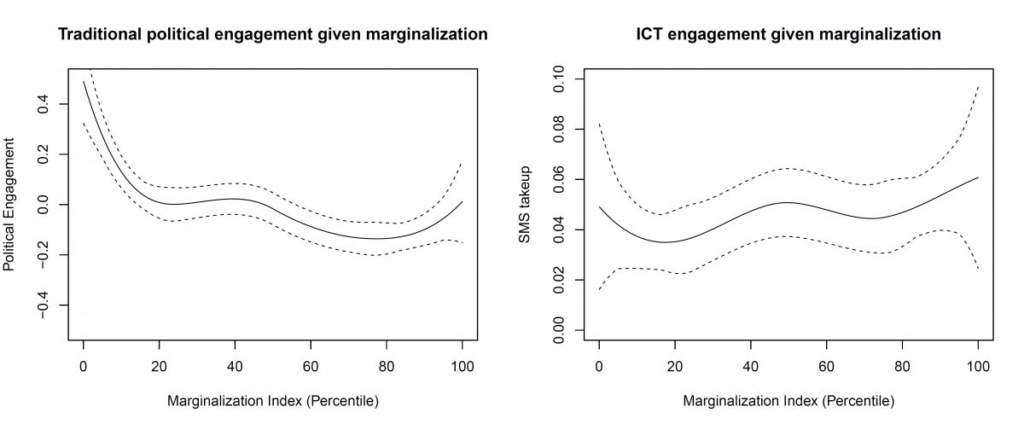

Strikingly, the authors found evidence that ICTs can have flattening effects: more marginal respondents engaged at high rates relative to others (especially as compared to differences in the use of other forms of communication) and the share of marginalized populations among the SMS sending group was a lot higher than among a comparably sized group of the most traditionally engaged subjects. Surprisingly though the authors did not find big differences in what was being communicated across these groups.

In the graph on the lefthand side in the figure below, we see that the rate of engagement using traditional means is a lot lower for more marginalized people. That downward slope cannot be seen on the right figure and if anything there is an upward slope, suggesting greater levels of ICT communication from more marginalized populations.

Price Effects:

Price did have an effect on uptake as predicted. Less expensive communication resulted in greater uptake. Specifically, moving from a partial subsidy to a free price or from a full price to a free price resulted in an increase in uptake of about 2 percentage points, or an approximately 50 percent increase.

Although one might expect the poor to be more sensitive to price changes, this was not the case here. The price effect on the poor (0.009) was in fact slightly smaller than the effect on the wealthier subjects (0.011), but this difference was not statistically distinguishable from zero.

There was no effect of price on the type of message (public or private) that subjects chose to send. This suggests that, contrary to the logic proposed above, message content was not a function of the subject’s perception of the number of other senders.

Policy Implications:

The authors conclude that new technology has the potential to improve the ability of the poor to communicate to their representatives. That effects who politicians hear from, although it might not affect what they hear about.

Price subsidies can increase participation, but there is no evidence here that that will lead to greater flattening.

Note from the authors: This research was supported in part by NSF Award #1260631.